Commercial Wargames and Experiential Learning

by Roger Mason PhD

Introduction

Albert Einstein is credited with the quote “Imagination is better than knowledge.” Knowledge can provide immediate answers, but imagination provides a horizon where the knowledge can be employed. This is certainly true with wargames. I do not believe that wargames are necessarily predictive, but they can limit the set of possibilities, especially when considering future scenarios. Wargames can also provide unique platforms for learning.

To evaluate these questions, it is important to examine the issues of the Black Box, evaluate how the end user may learn from games, explore what COTS games can provide, and finally offer a hybrid solution or game requirements not met by COTS products. To begin I think it is important to deal with the most common obstacle presented by critics of commercial games, the Black Box problem.

The Black Box

engaging in information and processes that would encumber the game’s flow. Although the Black Box is hidden, it is essential because it is the actual game.

To develop the “box”, the game designer must evaluate data, prioritize information, and develop assumptions. In commercial games, the designers are always balancing fidelity with playability. You would not replicate a complicated tasking order for air operations in a commercial game. This level of detail would not work. You can abstract it and that is where the talent of the commercial designer comes into play.

There are several questions posed by wargame consumers. Is this game realistic? Are the game systems assumptions accurate? Are there any inaccuracies or missing elements that invalidate the use of this game? These persons often point to specific issues that seem to support these concerns.

The function they are now requiring was not part of the original design. Secondly, commercial game critics often talk about a “lack of rigor” in the underlying design details. This is not a lack of rigor, but the result of mandated pragmatism required to produce a commercially viable game.

An excellent example is Mark Herman’s Gulf Strike game. It was used during the planning of the 1990-91 Persian Gulf War. Herman’s game was very realistic but not 100% accurate. In the after-action reports, it was concluded the availability and overall accuracy made it very useful in the absence of any alternatives. The game’s Black Box was sufficient for the requirement.

Recently, I heard a presentation by a game designer working for a large firm that produces wargames for government use. In the Q and A he was asked how they develop games, especially during shortened development cycles. He said the first step is to review what topical commercial games are available and mine them for ideas. These are the same games often referred to as “just hobby games.” Commercial games have their limitations but offer definite advantages and opportunities.

The Black Box problem of 1782

The Black Box problem of 1782

The problem of wargaming and black boxes is not new. This was precisely the problem faced by the Royal Navy in 1782. 1781 had been a particularly unsatisfying year. The French had defeated the Royal Navy in the Battle of the Virginia Capes. The defeat prevented the rescue of the British army trapped at Yorktown. The result was the surrender of the army and the loss of the American colonies. This also led to heated debates on possible operational shortcomings within the Royal Navy.

John Clerk was a successful merchant and landowner. Clerk became interested in studying the problem of naval tactics. He began his research by reading all the available memoirs of British admirals. He also supplemented his studies with maps and eventually began employing naval miniatures to test possible tactics. In 1782 Clerk published part one of a four-part essay called An Essay on Naval Tactics, Systematical and Historical. The essay included a detailed analysis of British naval engagements dating back to Elizabeth I. It stands as one of the first operations research projects in Western history.

Clerk’s essay was immediately attacked as a “Black Box” problem. The criticisms were classic Black Box objections. Clerk had never served as a naval officer. The basis for his assumptions were unclear. Clerk’s conclusions could not be validated. They posed a threat to any operation where the tactics might be employed. A formal board of inquiry was empaneled to evaluate Clerk’s conclusions.

In the meantime, admirals like Horatio Nelson were reading Clerk’s books. The board of inquiry concluded Clerk’s ideas had merit. Nelson’s tactics at Trafalgar followed Clerk’s suggestions. Clerk also developed the tactical concept of “crossing the T” to overwhelm an enemy. In 1782 Clerk was an outsider from the defense industry. He provided a methodology that revolutionized naval tactics.

Learning for the End User

When people talk about learning from wargames, they typically start by assuming having an interesting game is the best avenue to stimulate learning. This is a good start, but there is so much more. The most important issue impacting the use of wargames for learning is understanding how adults learn. This is the theory of andragogy as developed by Malcom Knowles.

How do adults learn?

How do adults learn?

Andragogy is the art and science of adult learning. Knowles identified several characteristics in adult learning. Adults are attracted to the immediacy of learning and the connection to application. Adults are most interested in what impacts their lives. They are drawn to problem-solving instead of content gathering. Finally, they use their experience as a foundation for learning. Wargames in a working environment fits well with these characteristics.

This approach is empowered by situation cognition theory as developed by John Brown, Allan Collens, and Paul Fugiud. They observed that knowledge comes through doing. The student learns best in a familiar environment using real-world tools.

The Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky observed that learning increases during socialization, where cross-pollination of thoughts and experiences can occur.

Wargaming offers experiential learning where students learn through doing. During this process, operant conditions may emerge. An example of operant conditioning is learning that touching a hot stove will burn your finger. In wargame terms, this might be the importance of logistics, or why guarding your flank is critical for survival. In domains like public safety or warfare real-world incidents rarely occur in a fashion where systematic training is possible. This is where wargames can fill the gap.

The student may never have developed an experience base for a critical event with a low frequency of occurrence. (Ex: Russian tactical battalion groups begin crossing the border into Estonia.) At every command level decision-makers may have no direct experience evaluating these conditions or solving the associated problems. Wargaming can provide synthetic experience, which provides a foundation for active problem-solving in a real-world crisis. This is the experience they can build through wargaming.

Wargames and Experiential Learning

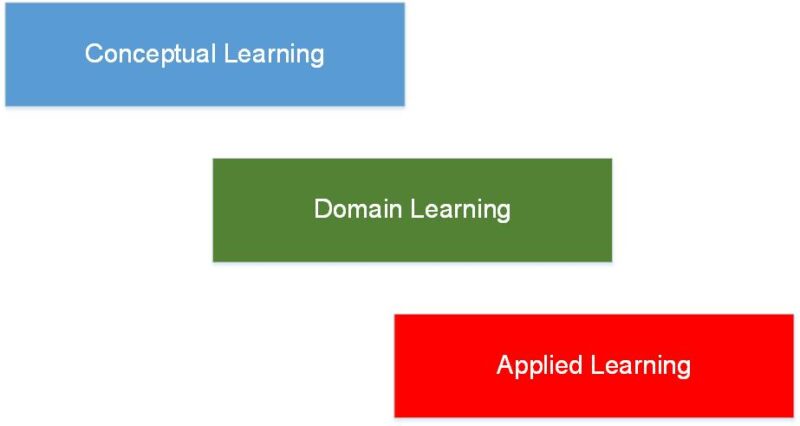

In 1984, D. A. Kolb published research on experience as the source of learning and development. He proposed there was a cycle of learning that progressed in four stages: Concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation.

Concrete experience involves doing or having an experience. During reflective observation, the student reflects on what he had experienced. Abstract conceptualization is where learning begins to root itself. The cycle concludes with active experimentation where the student employs what they have learned. Wargaming can easily fit into this cycle.

Differentiating purpose

One of the biggest problems when considering the value of games is first determining your purpose for the game. Are you using the game for learning or evaluating a problem? The black box critic may point out deficiencies because they intend the game as a tool for evaluating a course of action or better understanding a specific problem. This new purpose is something the game was originally never designed to do. This is a different goal than encouraging learning. If the game’s requirement is a specific problem, then it is better to design something specifically for that purpose.

Manual wargames versus computer games

Manual wargames versus computer games

There is an ongoing controversy about the use of manual versus computer wargames. For several decades designers of computer games have described their games as “serious” because they are played on high tech platforms, encourage immersion by the player, and hopefully encourage deeper learning through the experience. They are visually impressive and entertaining. Computer games can do these things well.

Computer games may accomplish their objectives too well. These games are typically designed as a single player experience. The immersion is often solitary immersion and the deeper learning objectives are unspecified. These games suffer the most from the Black Box evaluation because the technology is complex and requires extensive technical understanding.

Manual wargames encourage engagement instead of immersion. The immersion comes once the player groups are engaged. The engagement allows social learning to develop. Computer games are excellent at solitary problem-solving and task rehearsal. A good example is military professionals being defeated by teenagers who spend hours playing online games like Call to Arms. If you take the same teenagers and place them in front of a manual wargame, it is a different story. They are now confronting a unique situation involving multiple variables with uncertain outcomes.

Manual wargames are simpler tools encouraging group engagement and social learning. They cannot replace the high-tech capabilities of a computer game but they are far from obsolete. The debate regarding the appropriate tech levels for specific tasks is not a new problem. This is the reason the F-35 fighter has a gun. It is still possible to achieve complex objectives using low-tech tools.

Examples of Games

Examples of Games

In an average year 50-75 commercial wargames are published. There are lots of games of varying quality. Here are some types of games that should be considered.

Introductory Games

In the past twenty years, the micro wargame has emerged as a popular system. They have a small map with a handful of counters. The rules are simple, and the games are highly engageable. The topics range from classic battles to modern scenarios. These are a great tool for introducing people to wargames.

Classic Wargames

Classic wargames are often overlooked. The surge of 1960s-70s wargames produced by Avalon Hill and SPI provided the basis for contemporary manual wargames emerged from the original Avalon Hill and SPI games. James Dunnigan was responsible for many of these games. They are available on eBay and well worth considering. These are especially important for persons seeking to gather game design understanding and experience.

Topical Games

There are numerous topical games. Besides historical subjects, the games include modern and “what if” scenarios. Their sub-topics may include contemporary issues like hyperwar, network based operations, and cyber warfare.

Abstract and Experimental Games

Abstract and Experimental Games

Abstract and experimental games can be extremely useful platforms for learning. Brian Train’s Guerrilla Checkers employs a simple cloth map and a printed grid. There are two types of glass beads for playing pieces. The game is based on the guerilla strategies of Mao Zedong. Players quickly absorb the basic principles for Mao’s doctrines. It is brilliant in concept and simplicity.

The Possibilities of Multilayer Learning

What can be learned from commercial wargames? Are there layers of learning that can provide mutually supportive stratum? I believe there are three layers of learning possible within commercial wargames.

Three Layers of Learning

Conceptual Learning

The

Domain learning

Domain learning provides context to the student. In the case of the

profession of arms it allows you to study various historical and contemporary situations based on the context of the scenario. A student learns the universality of some problems contrasted with the unique nature of others. The games are more than just military history lessons. Expanding a student’s knowledge provides support and confirmation as they develop synthetic experiences.

Applied Learning

The application layer is where the student applies their conceptual skills, domain understanding, and experience into the game. The scenario offers an opportunity to apply what you know. You can employ what you have learned through experience against a new and possibly unique set of problems.

Characteristics of Successful Games

Familiar concepts and systems

Introducing persons to gaming is a gradual process. The games you present should have similar systems. Familiarity increases the engagement factor. Players that recognize a familiar game are more likely to jump in than with something foreign. Some commercial game companies offer series games that are different topics but use the same basic ruleset.

Visual and Tactile Familiarity

Visual and Tactile Familiarity

Familiarity draws people to games. They enjoy the sensation of moving pieces and playing with familiar artifacts such as cards. They like being able to look at the game board and quickly understand what the board/map represents. This approach also aids in player’s game orientation.

Ease of engagement

As a lifetime wargamer, I have an extensive collection of games. I have several amazing games that I have never played. The reason is their complexity daunts even experienced wargamers. There must be a balance between fidelity and playability.

If every possible game action involves a rule with qualifiers and variables, no one will want to play it. Without play. there is no learning. The games must be readily engageable. Engagement includes the speed of set up as well as understanding the game mechanisms. Games requiring extensive sets of rules are not a good choice for introducing students to wargaming. Cards can be useful because they can contain part of the ruleset and only come into play when the card is drawn.

Using briefing materials

A useful technique is preparing a short briefing paper about the game. A historical or situational background helps pique a potential player’s interest. Briefing materials should include the objective of the game..

A Hybrid Solution for Specific Problems

A Hybrid Solution for Specific Problems

There may be no commercial wargame that comes close to meeting your specific requirements. Here is a hybrid approach to solve the problem.

Employ experts for the design.

This level of game design expertise is hard to come by. Trying to design your own game without experience can be difficult. Consider employing a commercial game designer. One consideration is what if the designer does not have the appropriate security clearances. An experienced designer can build a game framework that will easily accommodate the addition of classified materials. Once the basic design has been submitted classified information can be added.

Identify the objectives

What are the objectives for this game? Everyone must be clear about what your objectives are.

Set the game

Setting the game means determining who the end-user will be and at what level the game will be played (tactical/operational/strategic.)

Focus on the requirements

Stay focused on the requirements. Is the game for training, evaluating performance, reviewing/developing a course of action, or analyzing a specific problem?

Establish a preliminary baseline

This is the baseline of data which serves as the source for rules, abstractions, and assumptions. This is the foundation for the game’s black box. This will become the framework for the game.

Summary

Summary

Wargaming is an excellent platform for experiential learning. The commercial game industry provides a great source of readily available games. A great source of readily available games is provided by the commercial game industry.

The Black Box issue remains a challenge but not an insurmountable obstacle. The successful employment of wargames as an active learning tool requires attention to the theories of how adults learn. Multi-layer designs can reinforce conceptual, domain, and applied learning.

As students play the games they are amassing basic conceptual skills, expanding their knowledge base, learning to evaluate problems in unfamiliar settings, and developing approaches to problem-solving. This can become a learning/experience feedback loop. As students develop greater synthetic experience, they are increasing their ability to solve problems. They can develop a methodology to organize real-world problems.

Wargaming can become a strong background for success when connected to real-world experiences, This brings us back to Einstein’s original observation. Perhaps the solution lies in the imagination of the application and not the collection of knowledge.