Designing Cyber Wargames

Roger Mason PhD

Modern conflict is standing at the horizon of information based warfare. For the foreseeable future, kinetic weapons will retain importance, but the control and manipulation of information will become pre-eminent. How can we design wargames for something that often seems as vague as cyberspace or the Internet? We are familiar with cyberspace, we interact with it constantly, and yet it seems difficult to explain.

This article is a basic introduction to the concept of cyber wargame design. I will explain how to understand cyber conflict using systems, describe the battlespace, learn to model multi-dimensionality, and explore combat and maneuver. I will also talk about applying conventional wargame design techniques to cyber games.

Systems and Cyber Conflict

All conflict simulations involve systems. My personal collection of wargames includes the first edition of Avalon Hill’s Battle of Gettysburg. The game uses a square grid mapping system with various units representing the Union and Confederate armies. A simple game that models several complex systems: types of weapons, different types of military units, movement, and terrain.

Modern warfare is undoubtedly more complicated than cavalry charges and musket volleys. Wargame designers must understand a variety of systems related to their scenario topic. Joseph Miranda’s commercial game titled Goeben 1914 is a good example. This is a historical solitaire simulation of the pursuit of the German dreadnought Goeben by the Royal Navy.

It is a relatively simple game which models some complex systems: the military situation, early 20th-century naval combat, political issues, functional requirements, emerging technologies, and decision making. In this game, Miranda has evaluated the systems that impacted the original situation, selected the most important, and organized them into a playable solitaire game.

Persons seeking to design cyber games must identify the related systems on several levels. One of the challenges is cyber effects can exist in reality by degrading or enhancing conventional systems, or as an operational schema that provide unique capabilities or threats. One of the problems of cyber wargame design is fixating on the cyberspace aspects first. Aspiring designers often give up in frustration because they “don’t know everything about cyberspace.” This ignores the fact that many successful wargames are designed by people with less than total knowledge about a game topic.

(Example: I have never flown a B-2 bomber, but I can include them in a game design.)

If your scenario topic involves conventional forces, this is where you should begin. I would do a traditional systems evaluation of the scenario, people, order of battle, conflict space, etc. Once that is complete, I would overlay whatever cyber effect or action may impact the conventional systems. Some examples include:

- Conventional operations requiring cyber effects to succeed.

- Conventional operations that can be enhanced or degraded by cyber effects.

- Direct or indirect effects/outcomes caused by cyber operations.

Once these effects have been identified the next step is estimating their impact on conventional systems. This can be difficult. Wargame designers have hard data on volumes of weapons systems, how they will perform, and probable effects against an enemy. This is much more difficult with cyber weapons and effects.

In conventional weapons, we tend to focus on the strength of the weapon and its potential impact on a target. Cyber effects require several aspects of evaluation. What impact will an application of the cyber effect have on enhancing or degrading a weapons system (Ex: did our “smart” precision munition just turn into a dumb bomb?). The secondary issue of connecting and friction points is also important.

Connecting points are the point where systems overlap and connect. Some kinetic and cyber effects represent a series of actions or events resulting in a positive military impact. These are sometimes referred to as “kill chains.” Friction points are where systems sometimes overlap and are sensitive to breakdowns.

Operational friction is caused by a variety of reasons from over-complexity to the reliability of the parts. Cyber wargame designers should balance their focus between understanding the conventional systems involved, evaluating the effects of cyber operations on these systems, and identifying the connection and friction points.

The Cyber Battlespace

The cyber battlespace is unique presenting considerable challenges to wargame designers. Cyberspace overlaps the “real world’ in the form of augmented reality. It is infinitely large and small. It offers a kind of teleportation that allows the user to instantly move anywhere within cyberspace.

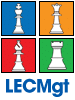

Cyberspace can be viewed as a parallel dimension. It cuts through the six natural operational domains common to conventional conflicts. The domains are earth, sea, air, space, and the electro-magnetic spectrum.

Within cyberspace and each of the natural domains is the possibility of five operational planes (command and control, persona, logical, and physical). These planes represent how people, software/applications, and physical location co-exist and impact one another. It is the overlay of the operational planes on natural domains and the augmented reality of a parallel universe that makes the job of wargame game designer so challenging.

Modeling Multi-Dimensionality

Our understanding of the cyber battlespace clearly indicates conflict will occur in and on multiple domains with dynamic operational planes. Cyberspace is multi-dimensional in form and how we think about. This includes mapping terrain, identifying centers of gravity, modeling operational plans, and accounting for time and space.

Mapping Terrain

Traditional wargame mapping involves transforming a three-dimensional space into a two-dimensional representation where playing pieces can mark their location and track movement. Wargame maps can also help to track space and time. Every Waterloo wargamer has anxiously counted hexes and looked at the turn track to see if the Prussians will arrive in time to tip the balance between victory and defeat.

Like many aspects of cyberspace, mapping terrain can seem both impossible and simple. For interesting reading try Googling “Mapping the Internet.” You will find volumes of competing studies attempting to develop a conceptual map of cyberspace. Cyberspace is the closest human architecture can come to designing infinity. If you focus on infinity wargame mapping of cyberspace is impossible.

What is possible is selecting a portion of the terrain and designing a map to represent it. You can develop a theoretical construct of what cyberspace looks like, but that will not be useful as a platform for wargaming. You still need a place for the players to interact and some type of map is best. Cyber wargame maps should be based on the unique nature of the domain and focus on places where conflict is most likely to appear.

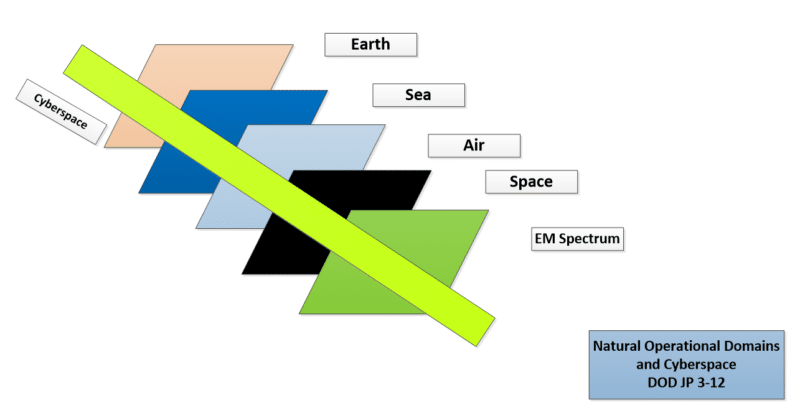

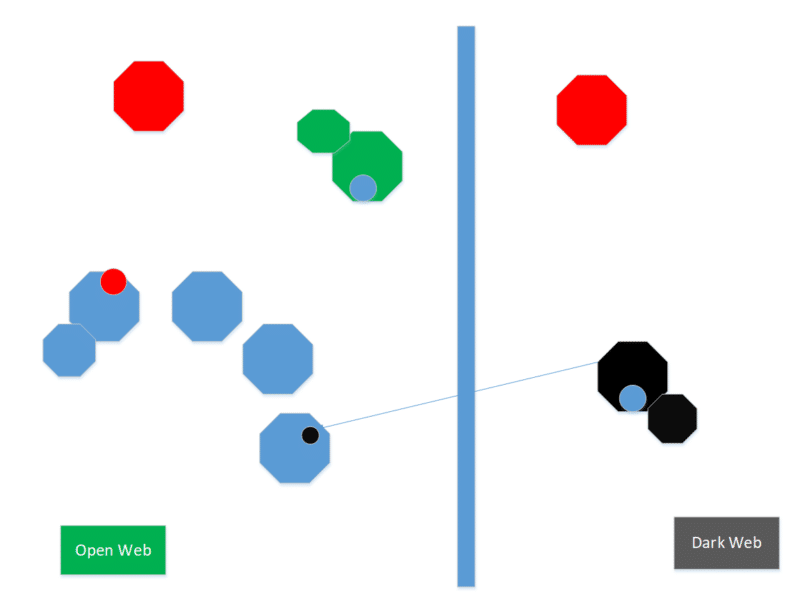

This simple diagram designed by Gregory Conti and David Raymon shows how the real world interacts with cyberspace.

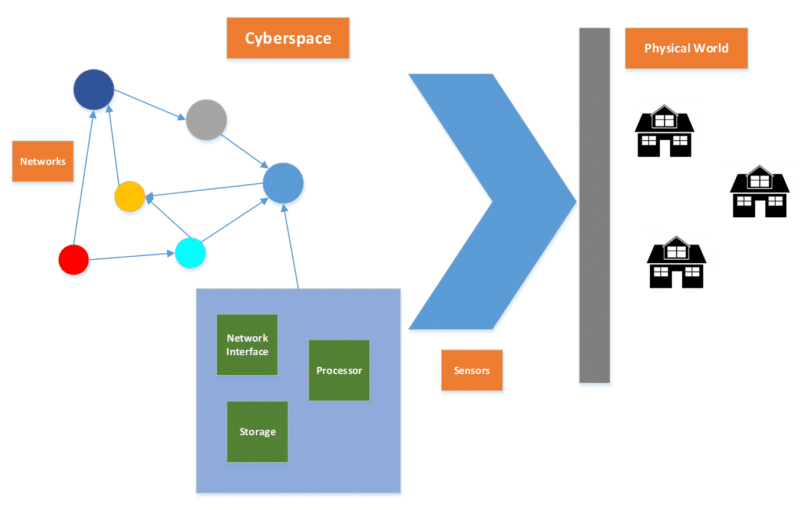

For the past six months, we have been experimenting with the concept of mapping cyberspace for wargaming. LECMgt’s chief wargame designer, Joseph Miranda, has developed a parallel mapping system. This involves overlaying the open and dark webs as parallel planes. Certain links in the form of a cyber-wormhole allow players to move from one web to the other. Offensive and defensive cyber functions can encourage or impede this movement. In this drawing the colored heptagons represent networks.

We have also experimented with mapping that portrays the two webs as adjacent on a single plane. Both systems allow the game designer to place something in a specific place in relation to other things on the plane. In this drawing, the two webs are adjacent, contain multiple networks, and offer inter-web movement.

Centers of Gravity

Clausewitz is famous for his concept of centers of gravity in warfare. Clausewitz defined centers of gravity as the most effective target where the greatest masses are concentrated. This concept is useful for game designers. You can’t map or model everything in cyberspace. Using the centers of gravity is a convenient way to focus your design parameters.

One way to identify the centers of gravity is determining where the most effective target is located. Is it with the network servers or the firewalls protecting them? Another possibility is determining the most sensitive network connection or the software needed to support a critical function.

Modeling Operational Planes

With five natural domains and four operational planes, things can get complicated. Conventional game designers have tackled this problem for some time. They employ off map locations that allow for the storage of units and extra-map operations. This technique can be applied to cyber games.

Time and Space

In a conventional wargame time and space are part of making the scenario real and interesting. A unique aspect of cyberspace is the ability to be anywhere and everywhere. It is similar to the sci-fi concept of teleportation. The problem of how far is the objective and how long will it take to reach has been replaced by presence. Where are the actors located in cyberspace? Can they maintain that presence or take some type of action in a specific domain on a particular plane?

Combat and Maneuver

Cyber warfare takes several forms such as enabling, enhancing, or degrading conventional military operations and operations directed at an opponent’s cyber operations. Cyber operations can be used to:

- Degrade network performance

- Disrupt cyber operations

- Enable/Prevent a course of action

- Divert a course of action

- Deny an opponent of the use of cyber operations

Games can be designed that provide players capabilities and the opportunities to employ them against an opponent.

Maneuver should be part of any cyber wargame. The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) is a process designed to standardize communications between computer systems. It was designed to ensure computers can quickly and easily talk to one another. This makes sharing data in cyberspace simple and opens the door to maneuver and combat.

Conventional maneuver such as frontal assaults, ambushes, and envelopments all occur in cyberspace. Cyber maneuver can occur in domains and on planes unique to cyberspace. Forces can move between networks, across domains, and into various operational planes. This makes cyber maneuver highly agile and due to anonymity and concealment difficult to stop.

Adversaries: More Than Us Versus Them

Wargame designers like things straightforward. Nothing is simpler than a conventional wargame with two clearly defined adversaries. Nothing can offer situation awareness like a wargame map with two sets of pieces in different colors. Cyber operations are different. The nature of cyber operations lends itself to hidden movement and concealment.

A conventional wargame design will involve a careful evaluation of each force involved. Cyber warfare will be littered with a variety of threat actors. These threats/forces may already be lying in wait or use the chaos of active conflict to launch attacks of opportunity. Designers should consider including collateral forces that may influence the game.

Should a cyber wargame only contain a pair of adversaries? The history of conventional wargaming is filled with games involving two opponents. This is not an accurate model of cyberspace. Cyberspace is a dynamic environment characterized by a variety of actors and threats who continuously change preferences, intentions, and loyalties.

A cyber game design must also represent other actors. The ease of access and the potential impact of even individual actors make them much more important they might have been in the past. No single person could have run out before Pickett’s charge and suddenly caused the Union cannons to simultaneously malfunction. The realities of cyberspace have increased the threat of individual actors.

Who are the actors that should be considered when designing cyber games? The list includes. Individuals, insider threats, hackers, criminals, political activists. Any of these individuals or groups are capable of initiating cyberspace operations.

An additional technique is to include autonomous networks in the design. An autonomous network is a game actor that is not under the control of the players. These types of networks can be included in a game using artificial life techniques demonstrating emergent behavior. In Cyber Crisis, a wargame designed by myself and Joseph Miranda, autonomous networks appear in the open and dark webs. They operate autonomously based on individual preferences, random effects, and sensitivity to the situational environment.

Developing an “Order of Battle”

A typical order of battle lists forces and their capabilities. The US Army defines an order of battle as listings that count and categorize forces in terms of unit type, quality, and quantity of armament. If your cyber wargame includes conventional forces it should also include their cyber capabilities. This means how cyber enhances operations and their possible vulnerabilities to a cyber-attack. This can also work for developing orders of battle for strictly cyber operations.

Applying Conventional Design Techniques

Applying Conventional Design Techniques

A question that is often raised is whether conventional wargame design techniques will work in cyber wargames. I believe the answer is yes. A cyber wargame still needs the basics.

- Map: Something to frame the game’s theater of action.

- Rules: Protocols that allow players to take and limit actions.

- Decision Making: Opportunities to develop a course of action.

- Consequences: Bad decisions should lead to adverse outcomes.

- Random Events: External situations that impact courses of action.

- Dilemmas: Problems that force players to make choices.

- The Story: A plausible scenario that brings the individual parts together and the game to life.

Types of Games

Designers should consider starting their efforts by employing one of the three conventional wargame systems: tabletop top games, seminars, and computer games.

- Tabletop Games: Easy to design and modify. Requires no technology. Promotes social learning. The game requires interactions by players to deal with game mechanics.

- Seminar Games: Easy to design. Promotes corporate decision making and problem-solving. Does not provide the systems detail of a tabletop or computer game.

- Computer Games: The game will handle the game mechanics. The game can portray cyber operations in a format that resembles the real world application. Computer games do not promote social learning. They are expensive to design, require technology to employ, and are difficult to modify.

Conclusion

Cyber operations in business, government, and political/military require careful analysis and understanding. Cyber wargaming can help to evaluate the issue, familiarize decision makers, provide a useful platform for decision making during real-world operations. Many people have asked me where they should start? Do they need to be qualified in all areas of information technology to design a cyber wargame? Are the only people qualified to design a cyber wargame IT experts?

My answer is you do not need to be an IT expert to design cyber wargames. You need to be familiar with wargame design and then study the cyber factors related to your scenario. The more that you know about cyberspace, the more you can model and simulate it in your games. Peter Perla has called cyber wargames the “Holy Grail” of future wargame design. I believe there are techniques that can be employed to successfully design cyber wargames. I am confident the next generation of wargames will include cyber games. In the meantime, I guess it means we are on a “Grail Quest.” A challenging but worthy endeavor.