Designing Homeland Security Games and Exercises

by Roger Mason PhD

Introduction

Homeland security games helped to introduce the concept of the professional wargame. In the 1950s the RAND Corporation began experimenting with games that modeled possible nuclear attacks on the US mainland. Since then, professional games have been used to evaluate and analyze a wide spectrum of political and military problems.

There seems to be interest in re-applying the rigor of wargaming to homeland security issues. This article will provide practical methods to design and evaluate homeland security games. It provides insights into how homeland security incidents are managed and organized. By adopting the same incident evaluation criterion as homeland security emergency managers, it is possible to develop a practical design template.

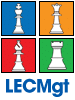

National Incident Management System

The National Incident Management System (NIMS) is the federal plan for managing homeland security incidents. There are five essential elements in NIMS related to game design.

Incident Command System (ICS): ICS is a standardized approach to managing emergencies and planned events. It is a hierarchical structure that can be increased or diminished depending on the size and criticality of the event. ICS enables a coordinated response by providing a common vocabulary and a standardized organizational template.

Unified Command: Unified command is designed to allow all responsible agencies representing different disciplines to establish a common set of objectives and develop a response strategy. The type of incident is evaluated and the agency with the most resources or direct expertise is usually selected to provide the Incident Commander.

Unified Command: Unified command is designed to allow all responsible agencies representing different disciplines to establish a common set of objectives and develop a response strategy. The type of incident is evaluated and the agency with the most resources or direct expertise is usually selected to provide the Incident Commander.

Incident Action Plan (IAP): The IAP is a written plan which establishes objectives, assigns resources, identifies a person in charge, and sets a timetable for completion.

Operational Period: The operational period is an established period of time in which the objectives of the IAP are employed. The operational period begins with a briefing of the IAP. Towards the end of the period the IAP objectives are evaluated. If they have been completed new objectives will be developed. If they have not been completed additional resources may be allocated to the objective.

Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP): The purpose of HSEEP is to provide a system for the design of exercises, methods for exercise evaluation, and a process for developing a recurring exercise cycle.

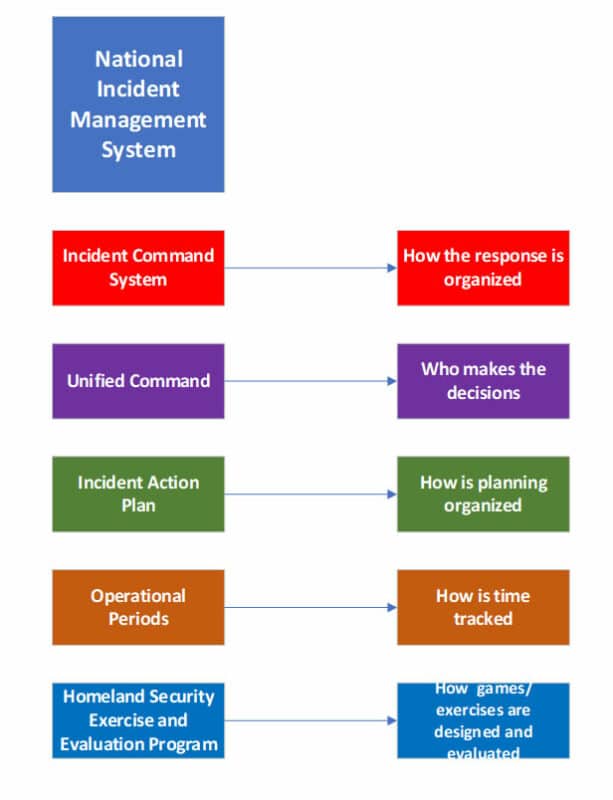

Disaster Cycle

There are six stages in the incident response cycle. A game designer must determine how their game will intersect within this cycle. The cycle moves clockwise from the initial response to stabilization and finally de-mobilization. The game can begin at any point on the cycle or focus on one of the stages.

Level of the Game

Level of the Game

The National Incident Management System employs three levels to describe the extent of resources and types of decisions at each level.

Operational: The operational level involves a wider area of impact and a greater commitment of resources. Operational decision makers coordinate the actions at the tactical level. The decision making involves directing the incident response and coordinating resources.

Strategic: The strategic level is about coordination and management of national resources. Strategic decision makers set priorities and provide direction to the operational level. The most important decisions involve setting objectives, tracking operations, and managing resources to support them.

Homeland Security Command and Control

When designing homeland security games, it is essential to understand how command and control works, who is in charge, at what level, and who will be involved in the response. There are federal laws that direct who can do what and limit certain actions.

Although the level and extent of command may change, the fundamental systems for organization remain constant. These systems fall under the guidelines of the Incident Command System (ICS).

Levels of Command and Control

There are three levels of command and control.

Tactical: There are two types of tactical command and control. The first is the initial response. ICS dictates that the first person on scene is the initial incident commander. They remain in charge of the scene until relieved by a person or greater rank and authority. The second type of tactical response may be actions at a limited location. In an incident like a fast-moving wildfire there may be several tactical operations occurring simultaneously. The person with the greatest rank and authority is in charge. In both cases the incident commander is responsible for the tactical situation.

Operational: Operational command and control have three responsibilities: overseeing tactical operations, tracking the entire incident, and managing resources. Operational command and control employ unified command where the responding stakeholders agree upon common objectives and share the decision-making.

Strategic: The strategic level is overseeing operations and managing resources, In a major disaster there may be several operations made up of numerous tactical events.

The strategic level decision makers leave the tactical oversight to the operational level.

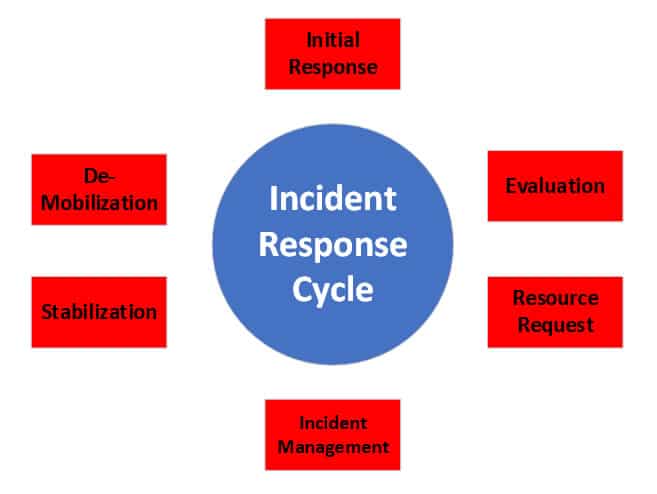

National Operations Centers

A unique aspect of the strategic level is many of the stakeholders are backed up by national operations centers within their parent organizations. These operations centers cover stakeholder organizations that have essential responsibilities to the homeland security mission. Many organizations have operations centers but there are eight of particular importance to homeland security.

HHS/CDC: The Health and Human Services Administration maintains an emergency operations center managed by the Centers for Disease Control.

DOE/NEST: The Department of Energy has an emergency operations center for the Nuclear Emergency Support Team (NEST). NEST provides an emergency response capability for any accidental or human caused nuclear incidents.

DHS/NOC: The Department of Homeland Security has a national operations center.

DOJ/SOC: The US Department of Justice (DOJ) has a special operations center for all federal law enforcement agencies, The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) is an operational component of the Department of Homeland Security. They provide the DOJ a national cybersecurity element in the operations center.

NIST/SOC: the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides national guidelines and standards for cybersecurity. NIST has a cyber special operations center.

USCG/NCC: The US Coast Guard is a component agency of the Department of Homeland Security. Their national command center oversees maritime and US port operations.

HLS SA/NOC: The Department of Homeland Security Office of Homeland Security Situational Awareness has a national operations center.

USDA/NIFC: The US Department of Agriculture manages wildfires at their National Interagency Fire Center.

Military Assistance: The US military plays an important part in responding to homeland security incidents. To accurately model these resources, it is essential to understand their rules for employment and organization. When the US military is involved in responding to disasters or emergencies these actions are labeled defense support of civil authorities (DSCA) operations.

DSCA operations can be accomplished by National Guard forces or the active or reserve components of the US military. National Guard units can be mobilized by state governors under US Title 32 which allows states to activate National Guard forces for state emergencies. US Title 10 allows the federal activation of National Guard units.

It is important to note that National Guard units are a state resource and not assigned as a local resource. There is no “Los Angeles National Guard.” There are California National Guard units located in Los Angeles.

Active duty and military reserve units can be deployed to disaster relief. The Posse Comitatus Act prevents active-duty units from enforcing the law but does not prevent them from assisting in disaster relief. (Ex: use of US Navy hospital ships during the Covid response.) During civil unrest National Guard units are activated under Title 32 so they can be used to enforce state law.

Incident Template

Most articles on developing homeland security wargames provide little practical direction. Emergency managers are a good resource for understanding how disasters are managed. There are six factors that emergency managers consider when evaluating a disaster. These factors can serve as a foundation for developing a HLS game design template.

Type

Homeland security incidents fall into three categories: natural disasters, human caused, and accidents. Natural disasters can include weather events, earthquakes, and wildfires caused by lightning. Human caused events include criminal acts and terrorism. Accidents include incidents like hazardous material spills or maritime disasters. While each type of disaster or emergency is unique, the methods to manage them are standardized.

Location

The location where the incident originates is a critical part of your scenario. The first question is the size of the area impacted by this event. Is it a localized flooding incident or a national security threat like the 9/11 attacks? The location of the incident and the severity of the impact will help you to set the game at one of four levels. The levels are: local, regional, state, and national. By setting the level of the scenario you can determine what agencies will be involved, what resources should be available, and what types of decisions should be included in the game.

Persistence represents how long the emergency will last. A national security event like the COVID outbreak had an extensive persistence factor lasting several years. Some incidents will be over quickly. Some emergencies have the possibility of secondary or cascading affects. For example, the US Geological Survey forecasts after a major earthquake the probability of numerous aftershocks capable of causing additional damage. The air traffic shutdown after 9/11 impacted the entire country but only lasted two days.

Incorporating the persistence factor is an important part of accurate modeling. It will impact the population and infrastructure you are modeling.

Population

The first step in evaluating the population is the number of casualties, the care level the population may require, and the need for possible evacuations. The next step is determining the needs of the population by evaluating the condition of the infrastructure needed for survival.

Infrastructure represents the functions needed to support a population after a disaster. They include sewer services, water, electricity, natural gas, fuel, transportation, and trash/solid waste removal. It can also include information services and communications.

Emergency managers employ a four-part system to evaluate the condition of infrastructure. They are:

1) Can it be repaired? (Is the damage limited so repairs are possible?)

2) Does it need to be replaced? (Is the damage so severe that repairs are impractical?)

3) Is the condition a combination of both? (Can some of the functional elements be repaired while others will require replacement?)

4) Are temporary workarounds possible? (Ex: Employing generators or delivering water)

Systems

Systems represent organizations and their capabilities. In homeland security games they can include governance, public safety, health services, and public works. An important part of post-disaster recovery is the availability of financial services.

Assessing the Results

After assessing the results, the designer should be able to answer four questions

- Who will be the game’s stakeholders?

- What are the great impacts of the threat?

- Based on the scenario, what problems can be anticipated?

- What decisions will need to be made and when in the game are they likely to occur?

It is essential these points are built into the game design.

Mapping

Geo-Spatial Map: This is the traditional terrain map used to indicate various locations and track the movement of units. This type of map is common at the tactical and operational level.

Situation Map: A situation map can be used to track a specific dynamic situation like the approach of a hurricane or the forward edge of an urban wildfire interface. In real world emergencies situational maps are developed at the operational level.

Timeline: Time management and awareness are essential skills for an emergency manager. Timelines are useful for tracking decisions and resources. At the tactical level the incident is managed with the resources at hand. At the operational level decision makers begin requesting additional resources, planning for their availability, and preparing for their employment. A timeline is useful in operational level games to track what was done and when it occurred.

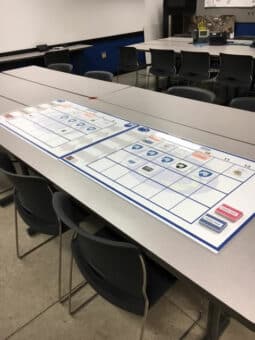

Dashboard: A dashboard is an operational map indicating the current conditions and capabilities of various functions. It displays the status of forces and levels of resources. A dashboard can be adapted to the operational or strategic level.

Time and Abstraction

Duration is the length of game time that an action takes. Duration can also be employed as a manipulative factor. By limiting a player’s actions or rewarding them with additional actions you can manipulate the impact of time within the game. The sequence of the game time can order events within the game. Time in the game also provides opportunities for problem-solving and decision-making.

Time can be modeled in two approaches which are time as a stream and fragmented time. Time as a stream is represented by Newton’s theory that time is absolute and progresses at a constant pace throughout the universe. This can be a constant pace of discreet sections of game time representing minutes, hours, or days. This should be mirrored by the level of the game. Tactical games can be played representing minutes while strategic game turns may represent days.

Fragmented game turns are designed to closely match the game objectives to the game play. The game time is fragmented by allowing for the ability to move forward in time between actions. This can be useful for facilitators if the game begins to bog down. They can announce the results of the last actions and tell the players they have now moved ahead in the scenario. This requires providing an update of the environment and game conditions. This allows the facilitator to keep the game moving to ensure you reach your objectives.

Abstractions are a useful tool for designers. A game abstraction is where a capability or circumstance caused by a situation, or an agent is inserted in the game without actually introducing the source. You get the value of the effect without having to develop game procedures to support it.

A good example is the national operations centers. Their influence may be very important in certain strategic level games. For example, an action by the National Interagency Fire Center may be represented by a random event. This may or may not occur during the game. If it does occur, by abstracting the effects, you get the advantage of introducing a decision the NIFC might make without needing to add another player to the game.

Validating the Design

Face Validation: Face validation means the wargame appears to represent the concept or situation the game is based on.

Content Validation: Content validation means the data game is based upon is correct.

Triangulation: Triangulation refers to the employment of separate groups, including subject matter experts, to evaluate the game design. The goal of triangulation is to reach consensus on the trustworthiness and credibility of the game’s design.

Type of Game

Putting the Game on the Table

After studying the elements and organizing your data it’s time to design the game.

There are eight steps to consider:

Determine Your Goals and Objectives

The starting point for any wargame design is determining your goals and objectives. The goal represents the end state you are seeking to achieve. The objectives are the specific elements you wish to address.

Develop the Scenario

The next step is the scenario. The scenario is the backstory which provides the context for game play. Be sure the scenario contains sufficient opportunities to achieve your objectives.

Decide where the game will fall on the disaster cycle

Remember the cycle designed in a clockwise progression. You can start from the beginning, go along the cycle, or focus on a single element.

Select the level of the game

You should select the level for the game. Once you do you can identify what forces and resources will be available and what decisions and dilemmas will be necessary.

Determine the type of game

For an accident or a natural disaster your game will be a solitaire game without a human adversary. This type of game can be played as a team effort with different players representing various stakeholders. For criminal acts or terrorism scenarios it is possible to use a red team approach with an active adversary.

Prepare the incident template

Take your scenario facts and you can build a model of the incident or event. The details can be added to your scenario.

Identify the type of maps

The purpose of your maps is to provide the players with a visual representation of the scenario, situational awareness, or an overview of capabilities and resources. Consider a combination of maps that offer good situational awareness.

Validate your design

Use qualitative methods to validate your design. Employ triangulation to achieve consensus about its trustworthiness.

Maintaining Balance, the Final Step

Maintaining Balance, the Final Step

The final step in designing a homeland security game is maintaining a balance between fidelity and playability. Fidelity is important. You want your design to be accurate and contain the essential elements that it is supposed to represent. It is also critical that the game is not so burdened with detail that it is unplayable. The balancing point is to focus on specifics that allow the game to reach its objectives while avoiding the extraneous which can limit player accessibility and engagement.

Summary

Homeland security games are a special niche in the professional gaming world. While sharing many of the traits of modern wargaming they retain some unique elements which require special care when designing them. The games must include the standardized processes and protocols employed by homeland security professionals.

Understanding the evaluation and analytic process of emergency managers can provide a realistic foundation for game designs. Designing homeland security games that provide realistic content and reasonable accessibility offers a cost-effective training and analysis tool for homeland security professionals.