Designing Public Safety Games and Tabletop Exercises

by Roger Mason PhD

Introduction

Introduction

Public Safety organizations employ tabletop style exercises to train their personnel. These exercises provide a flexible and cost-effective system to simulate a variety of critical incidents. This article will discuss how to design tabletop exercises and the next level of simulation complexity, wargames. I will discuss the uses of these exercises and the common and unique characteristics of each.

We will explore five steps for designing a game or exercise and how to validate the design. Some people maintain that tabletop exercises are simple to design because they appear to be simple. There may be more to designing a tabletop exercise or wargame than some people believe.

I. The Uses of Games and Tabletop Exercises

There are six uses for a wargame or tabletop exercise. These include evaluation, problem-solving, training, testing, and learning.

Evaluate a COA

Games and tabletop exercises are excellent tools for evaluating Courses of Action (COAs). COAs are predesigned plans for a specific type of contingency. Their value lays in having a plan in place instead of developing one as an incident unfolds. A wargame or exercise can evaluate various factors including the resources allocated to the plan, the logistics needed to support the plan, and the team designated to employ the plan.

Develop a COA

When a COA has not been prepared, a wargame or tabletop exercise can be used to test the plan during development. Factors such as resources, logistics, sequence of action, and how long each phase of the plan will take can be tested.

Many types of disasters or emergencies have a significant probability of occurring. The challenge is simulating these events is often impractical, expensive, and difficult to schedule. Sometimes, within a type of incident, there are specific problems that need to be addressed. A wargame or exercise can be designed to focus on a problem. The flexibility of a game or exercise allows the players to modify factors to evaluate the outcomes. Compared to a full functional exercise, the wargame or tabletop exercise is inexpensive, allowing it to be repeated.

Train a team

Training in the public safety domain involves constant change. Personnel changes can impact a team’s abilities. Requirements can change requiring modifications to procedures. A wargame or exercise allows participants to experience the changes and interact with them using active learning techniques. A wargame or tabletop exercise can allow teams to train in a risk-free environment making decisions, solving problems, and taking action in a simulated incident.

Evaluate a team

Wargames and tabletop exercises provide a direct way to evaluate the performance of a team. Team leaders can watch their team in a simulated incident. A well-designed game or exercise should offer realistic opportunities for decision-making and problem-solving. Games and exercises can reveal if the team understands the plan works.

Developing synthetic experience

Besides the five uses for games and tabletops there is an equally important benefit. This benefit is the development of synthetic experience. Real world incidents provide real world experience. Decision-makers rely on their experiences in uncertain situations. Their memory searches for any similar experiences and attempts to apply them to

problem-solving. When there are no experiences, the decision-maker relies on heuristics or trial and error. Persons who have specific wargame or tabletop experiences can substitute them in the absence of real world experience.

II. Games and Tabletops

II. Games and Tabletops

Wargames and tabletop exercises share many of the same elements and yet each has unique characteristics.

Elements of a tabletop

There are five elements of a tabletop exercise. The exercise is discussion-based, employs a scenario format, the participants typically represent real world actors, requires a facilitator, and supports role-playing. The scenario provides the context for the discussion. The participants represent real-world actors and base their decisions and problem-solving through role-playing.

The facilitator directs the discussion by focusing it on the scenario and overseeing the actions of the players. This may include limiting them to real-world actions with a realistic realm of possibilities. The limitations may include enforcing a realistic span of control or preventing outcomes beyond the boundaries of the scenario. Having practical limitations on decisions and solutions reinforces the feeling of realism.

Tabletop vs Focused Tabletop

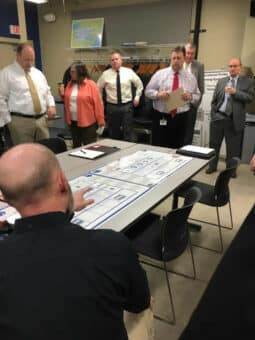

A focused tabletop includes some of the tools the players will employ in the real world. These include maps, charts, playing pieces, and timelines. As a result’ the player’s engagement is deeper and it is possible to make a clearer connection between problem-solving and decision-making. Players must manage visual data and take actions increasing realism. The exercise tools provide a focal point for players.

Focused tabletops require greater preparation than discussion-based tabletops. These exercises offer greater opportunities for post-event analysis. Tools like the maps and timelines are useful during debrief discussions. The exercise debrief can employ the same tools used in the game to track what took place.

What is a wargame? Dr. Peter Perla has defined wargames as “A warfare model or simulation that does not involve the operations of actual forces, and in which the flow of events shapes and is shaped by decisions made by a human player or players.” The elements of a wargame include the scenario, the objectives, foundational data, models, and rules. The goal of a wargame is to create a synthetic or virtual universe where the players solve problems, make decisions, and take actions.

When considering the use of wargames for public safety applications three questions which must be answered: what is a wargame, how does it differ from a tabletop exercise, and how can it be applied to public safety problems. Wargames have a long history of modeling military and political conflict. In military forces and governments wargaming remains a vital tool to understand and prepare for conflict. In the past forty years, wargaming techniques have also been applied to business problem-solving.

When considering what games and exercises can accomplish, a wargame and a tabletop exercise have some things in common. Both involve a scenario with problems for the players to evaluate and resolve. The greatest difference is a wargame tends to be more rigid than a tabletop exercise with specific rules governing a player’s actions. A wargame requires greater attention to accuracy than a tabletop exercise. The use of time, space, and interactions is more carefully defined.

How can you employ a public safety wargame? The effort needed to design an accurate and effective game is a barrier for most organizations. The most significant difference from public safety agencies and the military is their operational status. Public safety agencies are operational 24/7. Public safety personnel who participate in a wargame or tabletop exercise usually step out of operational status for the game and immediately return to operations once the game is complete.

This is both an advantage and a barrier to the use of wargames. The advantage is the persons designing the game usually have extensive operational experience. The people who will play the game will step out of their operational status so their experience with the game scenario can be as current as yesterday. The barrier comes in having the resources needed to design a wargame.

What is the best use for a public safety wargame? The best use of a public safety wargame is problem-solving. Wargames cannot provide the perfect answer, but they can help players to develop fresh methodologies and problem-solving alternatives which may be needed in a dynamic incident.

Most public safety wargames involve larger forces of responders requiring greater resources and logistics. A department wishing to evaluate response methods for a multi-residence fire can gain great insights from a tabletop exercise. If the scenario is a multiagency urban wildfire involving thousands of acres, a wargame may be more valuable.

In one regard, public safety wargaming is very different than political/military and business wargaming. Political/ military wargaming is played at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels. Many of these games are used to evaluate possible conditions and situations decades into the future. This is not the case in public safety wargaming. Public safety problem-solving is at the operational and tactical level in a local setting.

III. Five Steps for Getting Started

III. Five Steps for Getting Started

There are five steps for getting started with your wargame or exercise design. They are the setting (the purpose of the exercise) , the scenario ( background story for the exercise), time (time and action in the exercise), scaffolding (organizing the exercise), and avoiding red flags (design flaws that can ruin a game).

Setting: Purpose, client, scope, learning/analysis objectives

The first task in designing any public safety wargame or tabletop exercise is determining the game’s purpose. A convenient way to determine the purpose is to review what a game or exercise can accomplish in relation to your interests. Secondly, you must determine who the client is. The decision level of the client should match the level of the game. This ensures the problems they are solving match their real-world authority and responsibilities. For example first responders make tactical decisions and incident commanders are focused on operational/strategic decisions.

The scope of the game is one of the necessary limiting factors. A landscape artist employs the frame to limit the horizons of the picture. If you are designing an urban wildfire exercise for first responders, the scope might be the first four hours of the fire. If you expand the scope to a multi-day scenario it is unlikely the real-world actors in the first four hours will be the same a week later.

A sure method for limiting the value of your game or exercise is to provide a scenario and then let the players take it where it will go. When you determine the purpose of the game you can also establish critical engagement points. For example, what problems do you want your players to examine, or specific learning objectives do you wish to accomplish?

By determining the objectives before the game, you improve the chances of engaging them purposefully. Conversely, when you neglect identifying and planning your objectives you may not reach your goals. (Ex: Your exercise on traffic evacuations ends up stuck on the initial fire response.)

Scenario

The scenario is the set of events, or story that your game or exercise will be built upon. It provides the overall context of what problems the players will face. The scenario can be historic or fictional. If its historic, you must decide what part of the story you will employ as the playing field for your game. (Ex: you can’t have a tactical game from World War II with a scenario that encompasses five years of the war.)

If you design the scenario, there are two methods to developing the story. First, find a historical situation that can be adapted to your scenario. In your scenario development, you may only be able to appropriate some of the facts. The second method is to develop a fictional scenario that is directly related to your organization.

The next issue is pacing. Pacing allows you to draw out the time so the player can engage the game or exercise. This prevents overloading from the start. Pacing allows for environmental changes in the scenario to mature. In game and exercise terms, environmental changes are not changes in the weather. The environment is the conditions within the scenario where play occurs. (Ex: The scenario is a traffic evacuation. The environment is the road net the game is played on and conditions such as weather that impact actions).

How do you connect the scenario to your game or exercise objectives? Many people develop a scenario and hope that the players will either solve the problems of interest or follow procedures as expected. This approach can sometimes work, but there is a greater likelihood of mixed or inconclusive results. The use of scenario typing can improve the odds of meeting your objectives. Scenario typing considers your objectives and matches potential player actions.

A problem-solving/decision-making scenario involves providing the players a set of unique contingencies. These types of problems requiring active problem-solving combined with timely decision-making leading are intended to stimulate action. This type of scenario works well when introducing new problems or situations. Finally, it is possible to mix procedures and protocols scenarios with problem-solving and decision-making. This is done by altering the scenario details requiring players to modify established plans to meet situational changes. A familiar example will help explain the typing process.

Your scenario is the sinking of the Titanic. The first possibility is an exercise that focuses on plans and procedures. In this case, the procedures involve evaluating the ship’s seaworthiness and launching the lifeboats. The second possibility is an active problem-solving/decision-making scenario. You have procedures to launch the lifeboats, but the ship is listing, preventing half of the boats to be launched. You present the players with problems requiring solutions and decisions. The players must prioritize who will be saved in the useable boats and what options are available to launch the remaining boats.

The third type of scenario offers a mixture of plans and procedures with problem-solving and decision-making. The plans and procedures begin with the decision to abandon ship. This sets the scenario in a specific direction. The initial solution pathway must be reconsidered as the ship begins to list. The change in conditions breaks down the initial plan requiring a re-focus on problem-solving and decision-making.

Time

In a game or exercise time can serve as part of the framework to which other important factors such as the setting and the scenario can be attached. This can be accomplished by identifying what type of decision and action opportunities you wish to provide and evaluating how long these would take to occur in the real world.

This requires examining the real-world events you are modeling. Take the scenario you are considering and consider the purpose and scope of the exercise. Then apply the scope to the actual event and determine what is possible within various periods of time. In evaluating an incident, the shorter the period of time, the lower the level of the model, and the greater the granularity of the actions.

For example, considering the initial response to a mass casualty event might cover the first 30 minutes of the incident. In this type of real-world incident, the initial response is always at the lowest or tactical decision level. Operational and strategic decision-makers will not be on the scene. Take the time period you are modeling and divide it into discrete sections, in this case, five decision periods each representing six minutes.

Look at your scope and determine what actions might be possible during the first 30 minutes of the incident. Next prioritize them and divide them into the five decision periods. This provides a specific baseline of what you hope the players will accomplish and in what order should it occur. Finally, design your scenario and injects so the players have the opportunity to develop solutions for these problems.

Scaffolding: Putting the pieces together

The process of designing a wargame or exercise can quickly become a complicated task with overlapping objectives and potentially conflicting details. The easiest way to organize the effort is to use a form of visual mapping. This technique can be referred to as scaffolding because like a building scaffold, it provides access to the framework of the building as it grows. Scaffolding is very similar to the storyboard process used by movie producers to visually track actions and elements in a movie script.

The scaffold is built upon the discreet subsections of time (decision periods), situational injects that cause changes to the game environment, and what you expect should occur. The expectations should be connected to your exercise objectives. This does not mean they will occur but including them helps you introduce changes or conditions that should prompt the players.

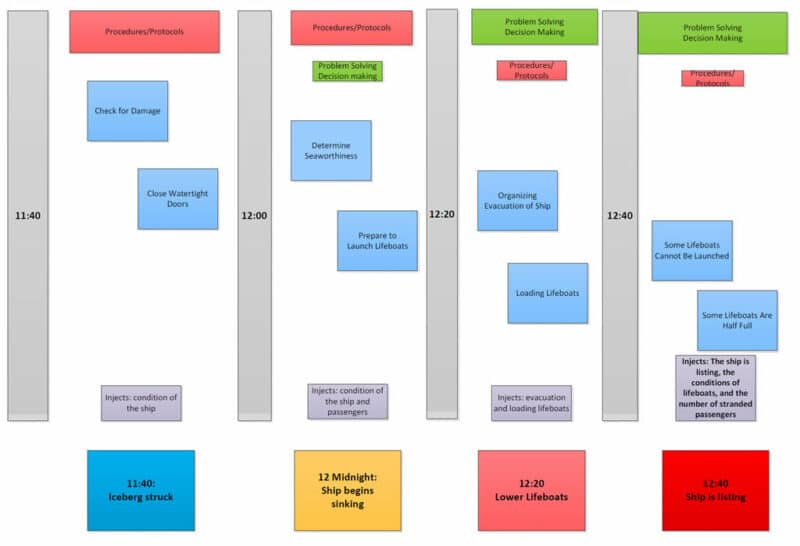

Here is an example using our Titanic scenario employing a combined procedures/protocols and problem-solving/decision-making exercise.

In the actual event the decision-makers had very little time to make decisions.

The blocks across the bottom summarize events and track criticality in each decision period. Across the top of the storyboard are boxes indicating what type of action is being emphasized. In the first decision period protocols and procedures are paramount. This is supported by the injects providing information about the condition of the ship. The two critical procedures were checking the ship for damage and closing the watertight doors.

In the next period, procedures and protocols are slightly less important as the initial problem-solving and decision-making begins to occur. This represents contingencies that are slightly outside the parameters of pre-established plans. The two critical factors are determining the seaworthiness of the ship and preparing to launch lifeboats. The injects will influence these procedures by providing the condition of the ship and the passengers.

By decision period three problem-solving and decision-making have surpassed procedures and protocols. The two biggest problems are organizing the evacuation and loading the lifeboats. This is not going as planned. These issues will be influenced by information in the injects. (Example: the preparation for launching the lifeboats is sporadic and disorganized.)

By decision period four procedures and protocols have been eclipsed by problem-solving and decision-making. Yet, almost nothing is going according to plan. The injects have increased. The ship is listing, and many passengers are stranded. The problems include the inability to launch some lifeboats and the fact many lifeboats are only half full.

By visually scaffolding the exercise, the designer can ensure they are meeting their objectives. In this case, you can track what is important within the exercise and when it occurs. You can see what type of action is being emphasized at what point. You can view the injects and how they influence the game. Finally, the blocks across the bottom help you to follow the progression of criticality within the scenario.

Avoiding “Red Flags”

While fidelity is important, including too many details or problems can be dangerous. These details can overcomplicate the exercise to a point where it becomes unplayable. Maintaining a balance between the two factors is critical in any successful game or exercise. Another red flag closely related to fidelity and playability is accessibility.

How clearly the players understand how the exercise is organized and what you are trying to accomplish is defined as accessibility. It is doubtful you will have a successful outcome when accessibility is limited, and the game is overly complicated. The third red flag is the doomsday scenario.

A game or exercise can have a good balance between fidelity and playability. The organization and objectives can be clear. The doomsday scenario can override these advantages and prevent a successful outcome. A doomsday scenario is a situation where the problems in the game are so overwhelming that the players give up. This can be a single problem beyond a player’s simulated resources or so many problems that they become impossible to resolve. After you design your game or exercise, the next question is how to validate it.

IV. Validating Wargames and Exercises

Is it essential to validate your wargame or exercise design, and is this possible? It is important to offer some type of validation to ensure people have confidence in your game. Scientific validation follows a series of steps from observations, developing a hypothesis, and testing with an experiment. A key indicator of validation is the ability to duplicate your experiment and achieve the same results.

This is not possible with a wargame or tabletop exercise. Experimental control is difficult as autonomous players make decisions that influence outcome variables. By introducing human decision-making into the process, duplication of results becomes impossible. What type of validation is possible for wargames and exercises?

Three types of validity should be considered. These forms of validity represent different things depending on how they are used in different domains. The types are face validity, content validity, and construct validity. Face validity means the game or exercise accurately models a real-world event. This is important in a public safety game where the players may be very familiar with the scenario topic. If you are devising a scenario, it is useful to research similar real-world events. The game scenario will offer a form of face validity because this type of incident has occurred.

Construct validity represents how accurately the game models the underlying concepts of this incident. These concepts can be physical such as wildfire dynamics or procedures involving standardized tactics the players are expected to employ. The scenario should support familiar concepts and conditions. There should be opportunities to employ tactics and procedures players have been trained to use.

Is predictive validity possible? Can a wargame or tabletop exercise predict real world events based on game outcomes? There have been famous wargames that accurately predicted the future, but these examples are rare. While games and exercises cannot predict the future, they can help to narrow the number of probable outcomes or possible end states.

Summary

Wargames and tabletop exercises are valuable tools for public safety decision-makers. They offer a variety of options, including planning, evaluations, training, and problem-solving. Game and exercise outcomes cannot predict the future, but they can narrow the possibilities of how the future may look. They offer public safety organizations the ability to prepare their current and future leaders with synthetic experiences. These experiences can fill the decision gap between real world experience and guessing during a critical incident.

Are games and exercises simple to design? Devising something that models a critical incident in a format where a training or evaluation simulation is possible is difficult. The complexity of your design should not be in the details of the model but the interactions that emerge. The point of emergence is where the deepest learning occurs. I think Aristotle said it best, “The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.” So, it is with designing games and exercises.