Evaluating Wargames

by Roger Mason PhD

As the demand for more professional wargames increases, it is essential to develop a simple methodology for evaluating them. This methodology provides consistency in form and organization in analysis and is repeatable. The secret to evaluation is considering the game from a strategic vantage point and gradually breaking each part down into individual elements.

So, what is a game, and how can we evaluate it? In their book Rules of Play, Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman state, “A game is a system in which players engage in artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome.” A subset of games are wargames or conflict simulations. Dr. Peter Perla defines a wargame as a representation of conflict “using rules, data and procedures in which the flow of events is determined by the decisions of the players.”

What is the best approach to evaluating a wargame? When evaluating a wargame ten areas should be considered. They include the game objectives, the narrative, models employed in the game, systems, the battlespace, the simulation, the game architecture, the content, playtesting, and design validation. Breaking a game down into these elements provides a method for evaluation.

1. Objectives

- Evaluating a course of action

- Developing a course of action

- Training a team

- Evaluating a team

- Evaluating an adversary

- Analyzing a problem

A pre-determined plan is known as a course of action. In a particular situation or circumstances Wargames are useful in evaluating and developing courses of action. The next two objectives involve teams. Wargames can be used to train a team to a course of action or set of procedures or evaluate their readiness to employ them.

Wargames can be helpful in evaluating an enemy. Games provide a flexible approach for appraising the elements of an adversary’s possible intentions, strategies, and capabilities. They are also valuable in analyzing specific problems by offering a convenient method for examination and analytical manipulation. Determining if a game meets its objectives may not be possible before completing the entire evaluation. As you evaluate each element of the game, the issue of objective fulfillment will become clearer.

2. Narrative

Narratives help us to understand the world around us. People employ narratives to describe various circumstances and ideas from daily life to stories about fictional worlds. Game narratives provide the foundation for an artificial world where the player must evaluate data, make decisions, and act. There are five elements in a professional game: the initial scenario, the objective(s), resources to achieve the objective(s), factors that alter the game environment, and uncertainty. In an effective game each element must relate to the narrative.

The three most common narratives are linear, adventure, and branch and gate. Linear narratives are a steady progression of predetermined events that influence the game. Adventure narratives provide the players with facts that provide a back story. An adventure narrative offers context for the elements in the game and serves as a starting point for the game. A branch and gate narrative branches out to gates or decision points. The player must resolve challenges at the decision points while moving through the narrative.

In Albert Van Der Meer’s essay on the structure of narration in games, the author identifies various forms of narration. Van Der Meer suggests the critical part of the narrative is the agency the narrative lends the players. He defines agency as the amount of freedom a player has to determine their actions and the game’s outcome.

The narrative appears in two forms: embedded and emergent. Embedded narratives are facts that are built into the game and are unchangeable. Emergent narratives occur as the players interact in various situations and conditions. This fits into network theory, where players have a single objective but may follow many paths.

Evaluation of the narrative serves three purposes. It helps the evaluator to understand what the game is about. The quality and relation of the narrative to the parts of the game should emerge throughout your evaluation. Secondly, it will demonstrate how the narrative is connected to the elements comprising the game. Finally, it will be the starting point when considering the validation of the game design.

3. Models

In wargames a model approximates a situation, system, or group of behaviors. A model represents the elements that will be manipulated during the simulation. Evaluating a wargame requires understanding the model(s) the game is intended to represent. As each model is evaluated, it provides context for what the game represents. Common wargame models include:

- Situations

- Systems

- Groups

- Behaviors

- Capabilities

Three modified forms of validation can be employed in wargames. Face validation occurs when the model appears to represent its real-world counterpart. Content validation considers the model’s content and whether the critical elements of the real-world counterpart are included. Construct validity considers the performance of the model. Does the model work?

Beyond functioning individually, a model must successfully interact with the other models. They must serve as mutually supportive elements. No matter how accurately the model is rendered in the game it must function with its surrounding models.

4. Systems

Webster defines a system as “an interdependent group of items forming a unified whole.” MIT lecturer and author Peter Senge observed that systems are based on interdependencies. Systems in a wargame represent the building blocks of the game models. The good news is most wargames include identical or similar systems.

Systems in wargames are the connecting points for the game design elements. In a wargame these systems often include:

- Combat

- Movement

- Logistics

- Intelligence/Sensors

- Communications

Other systems to consider include the battlespace (the representation of real space where the game is played) and the rule system.

A helpful method for evaluating these systems begins with listing the game systems. This list will also be useful during the playtest. Three questions should be considered. Is the function of the system understandable? Is it clear to the players what the system is intended to do? Secondly, do the systems in the game support the narrative? Finally, do the systems complement one another? The systems should be like a mosaic coexisting seamlessly within the game.

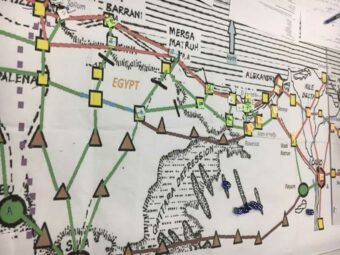

5. Battlespace

Most wargames contain five types of battlespace terrain:

- Conventional

- Multi-dimensional

- Abstract

- Representational

- Conceptual

Conventional terrain contains features on a single dimensional surface such as ground terrain and naval terrain. Multi-dimensional terrain can combine conventional terrain with domains such as the electromagnetic spectrum and space. It can also connect or group terrain on different levels.

Abstract battlespace can be represented by space where actions and interactions can occur. Abstract terrain occurs in domains lacking specific features that provide a spatial context. They include cyber space, outer space, and some underwater operations. It is still necessary to provide a spatial/relational orientation (where am I, where is the enemy?). Representational terrain is not a spatial domain but it orients conditions, and resources. It may affect action on multiple domains and is abstracted in the form of outcomes.

An important factor in evaluating the battlespace is its relationship to the game narrative. The battlespace must provide a simulation space that exhibits the unique aspects of the narrative. It should provide an opportunity to meet the game’s objectives,

The battlespace focuses the game by setting exterior limits on the simulation. The players will be confined to the space represented by the game map.

In conventional ground terrain there are two types of terrain. They are natural (vegetation, water features, ground condition, and elevation changes) and human-made (roads, fortifications, and structures.) Early commercial wargames like Tactics II had limited terrain features. The mapping in the battlespace looked like a plateau on the artic circle. The map was plain and featureless. One qualitative point of evaluation should be the appearance of the terrain on the map. Is it easy to differentiate and does it attract the players’ attention?

The terrain’ s time/spatial relationship should be considered. This can be determined by considering the simulated distance on the map and the movement rate of the units. The time and space must be balanced so units can access different parts of the board and engage in actions within the game time. There must be sufficient time for units to engage in positions across battlespace.

6. Simulation

An example of a multi-level simulation is a game where the movement of units are tracked on a map and the condition of individual units is tracked on a dashboard. The dashboard provides information about the units positioned on the map. A multi-level simulation combines the positional relationship of the units and their condition and capabilities.

Another aspect in evaluating a simulation is the mechanics of the game. The mechanics include the rules that structure the play. The rules must be carefully reviewed by the evaluator. The rules should be divided into three parts: basic rules, secondary rules, and optional rules. Basic rules regulate and direct the forms of play. Secondary rules involve situations the players may choose or experience. Optional rules represent options the players may select to modify or enhance play.

Other essential parts of a simulation include how game information is provided, how time is measured, and how conflict contacts are adjudicated. Rules can be provided in written form or situationally by drawing cards that introduce information relating to the rules.

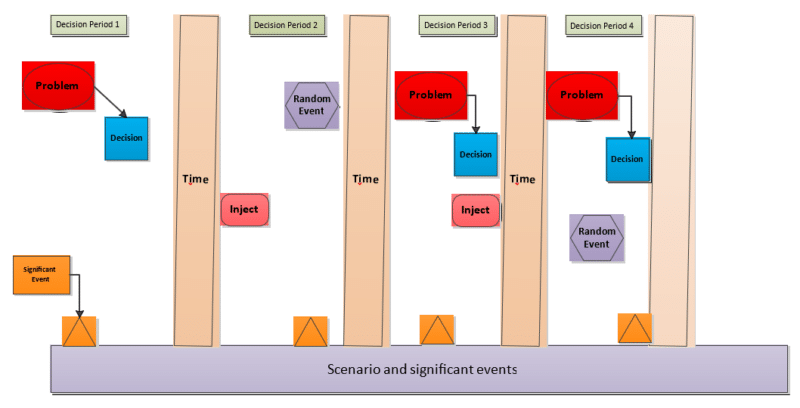

7. Game Architecture

A game’s architecture involves how the parts of the game are presented during the simulation. There are three parts to the architecture of a wargame: narrative, action, and time. The narrative provides the back story and context for the elements of the game. Action involves game induced events and player operations. Time is the temporal configuration that determines when actions occur.

8. Content

The informational foundation of a wargame is based on the content. Wargames are fictional, historical, or hypothetical. A fictional foundation is based on a set of facts artificially developed for the game. A historical foundation is based on historical events. A hypothetical game foundation can be a combination of fictional and real events.

When evaluating a historical game, it is important to determine if the game retains enough historical details to accurately model the original event. Hypothetical games require the same rigor as historical games. The supporting data may be limited, but the designer should attempt to model as much as the data will support accurately.

The players must be able to understand the information and connect with it. This connection is based on prior knowledge and experiences. The content of a fictional game may be familiar to the players, but the game must contain the elements of face and construct validity.

9. Playtesting

Each system in the game should be tested. The basic systems include movement, combat, logistics, and any potential environmental changes such as weather. Evaluators should set up a game scenario where each of these elements might occur. Next the battle space should be considered. Does the artificial game space accommodate these various systems? Another important aspect of playtesting is evaluating the opening moves of the game. Can the players engage with the game elements and operate within the battlespace?

10. Validation

An important tool in evaluating a wargame is by seeking to validate the design. A wargame cannot be validated employing scientific rules. The outcomes from identical conditions can result in widely varying outcomes. So what form of validation is possible? There are three forms of validation that can provide a sense of the game’s validity. They are face, content and action validation.

Face validation is the simplest and most superficial form of validation. Does the game look like the scenario it is intended to represent? Face validation is subjective because it is based on the impressions of an observer. It is still important because it is the first form of validation in nearly every case. People will evaluate a game by looking at it. If it does not provide a sense the game matches the scenario and narrative, then the observer is unlikely to continue their evaluation.

Content validation is a comparison of the real-world example and the models within the game. The second step is an evaluation of the data and materials used to support the narrative and development of the scenario. Action validation is used to evaluate the accuracy of the models and determine if the game play is realistic.

Summary

Summary

By creating a methodology for evaluating wargames we gain the advantages of standardization. By standardizing our methods, it is possible to improve the depth of our analysis. This may be a small but valuable step in the constant effort to professionalize the practice of wargaming.