Facilitating Tabletop Exercises

by Roger Mason PhD

Introduction

I have met many different facilitators with different styles and techniques. Some very successful facilitators use a casual approach relying on the brilliance of the exercise design and the spontaneous generation of solutions to overcome problems. Other facilitators use a more organized approach where the parts of the exercise experience are evaluated beforehand, and solutions are formulated. Translating personal brilliance to individual performance is difficult so this paper will provide some practical steps to improve your facilitation skills.

(Author’s Note: The reader should consider the use of the term participant or player as meaning the same thing, a person directly involved in the exercise.)

Preparation

As a facilitator there are three steps to prepare for a tabletop exercise. They are the topic, the exercise, and the organization of the event.

Topic

One of the most important parts of the tabletop design process is understanding the topic the exercise is designed to explore. The topic may be something you are familiar with or new and unfamiliar. During your design process many designers stay tightly focused on the topic they are modeling. I recommend taking a bit of time to look beyond the narrow topic and expanding your understanding of the context and associated topics. You do not need to become a subject matter expert but having a general understanding of what you are modeling will be useful.

I have a “game day” ritual I always follow. I leave early and drive to wherever I am facilitating the exercises. I find a coffee shop with Wi-Fi and google my topic. I am looking to see if anything related to my topic has occurred overnight. I buy a local newspaper and scan it for anything related to my topic. I often discover the local city council has authorized funds to address the topic of the exercise or a citizens group is calling for action related to the issue. This information will become part of the exercise dialog, so it helps to be prepared.

Exercise Prep

It is important to understand exactly how the exercise works. Much of the time facilitators were part of the design team and they are well prepared. You may be asked to facilitate an exercise you did not design. It is essential that you are aware of everything built into the design. This should not be done the morning of the exercise. You should take a few days to read through any background materials. This provides time to call members of the design team to clarify questions.

Event Organization

If possible, visit the location where the exercise will be held. This is especially important if the location is unfamiliar. As facilitator your job may or may not involve organizing the event. If you are just facilitating it is important to be familiar with the operational aspects of the event. (E.g., what is the WIFI password or where is the key to the restroom.)

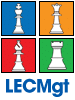

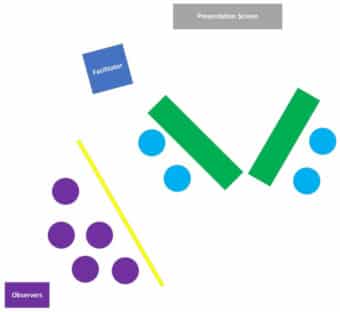

Room Setup

Seminar

The seminar set up has the participants in a mutually accessible configuration. They are seated at tables to allow them to take notes or place documents in front of them. If there are observers, they are off to one side. The observer seating area is divided from the exercise participants by a rope barrier.

The hybrid tabletop is similar to the seminar except the players cluster around a common table where they share information and manipulate exercise pieces such as a map or timeline.

Your Audience

Most tabletop top events are not open to the public. In this context my use of the term audience refers to the participants. There are four aspects of the audience. The participants. subs, observations, and dealing with “add ons.”

Participants

It is important to know who will be participating in the tabletop. As facilitator you need to know the level of the players and their experience. Are the participants executive decision makers in a policy group or recently promoted supervisors? Are the participants new to the topic or seasoned operators? The facilitator must anticipate these factors as they will impact exercise decisions and actions.

Subs

On many occasions I have been engaged in designing a tabletop for a specific group. The sponsor often wants the exercise to include the internal dynamics of the group. The morning of the exercise I discover the vice president for operations has a scheduling conflict. They have sent a newly promoted administrator to fill their place. This person is unfamiliar with the role they will be playing. A seasoned facilitator must be prepared to pivot their plans and expectations. This is not the fault of the substitute, and they may require more assistance than you expected.

Observations: Reading the room

I always try to build a few minutes before the exercises for observing the players. A simple tool is offering coffee and pastries. I watch how they converse and in which groups they collect. If the group is a military or quasi-military organization, I have already familiarized myself with any symbols indicating their ranks. Do they dress in civilian clothes or uniforms?

Sometimes individuals in specific career paths will dress to represent who they are (E.g., pilots dressed in flight suits with a laptop in their helmet bag, medical administrators wearing scrubs.) The pilots are not flying anywhere, and the administrators are not treating any patients but they still dress based on how they see themselves. All these things can provide the facilitator with insights about who they are.

Dealing with “Add Ons”

“Add Ons” occur when you have planned a tabletop for five and twenty people show up. You do not want to turn them away. I take the extra people and tell them they will be assisting the facilitator by observing the exercise and sharing their observations during the hotwash. I set up a rope line next to the exercise area. This serves as a barrier between them and the exercise players. During the exercise, the facilitator should interact with the observers to discuss what they are observing. This method offers a measure of engagement and prevents enthusiastic people from feeling left out.

Tools of the Facilitator

- Your business cards

- Printed lists of documentation items

- Clipboard

- Blank notebook

- Extra ballpoint pens

- Dry erase markers

- Dry erase white board eraser

- Sharpie pens (red, blue, green, black)

- Adhesive sketch pad (25”x30”)

- Laptop

- tape (one roll of adhesive, painters, and duct tape)

- Batteries (double A, triple A, D)

- Power strip with 36” cord

- Extension cord 10’

- Portable charger power bank with charging cord

- Yellow rope (20’) This is used as a crowd barrier.

You carry everything (except the adhesive sketch pad) in a small roller bag.

Tracking the Action

The facilitator should be tracking the action as the exercise progresses. This includes the goals and objectives, the time, and the player dynamics.

Goals and Objectives

Your tabletop exercise was designed with specific goals and objectives. The facilitator must keep them in mind and prevent the exercise from going in a direction that does not meet those goals and objectives.

Time

The facilitator is the exercise timekeeper. They must balance the flow of play and the goals and objectives against the time available. This is easier to accomplish with exercises divided into decision periods where distinct periods of time can be assigned. E.g., a one-hour exercise divided into three, twenty-minute decision periods. An exercise employing a continuous flow of decision and action requires constant monitoring to ensure goals and objectives are met.

Player Dynamics

During the exercise it is important to monitor the player dynamics. Player dynamics involves communications, body language, group problem-solving, and decision-making.

Your job is to ensure the player’s conduct is such that communications are open, and players are participating in the exercise functions.

Documentation

Documentation

As facilitator you may be asked to provide verbal or written comments regarding the conduct of the exercise, observations about the participants, or outcomes. It is important to keep detailed notes during the exercise. The most important rule to remember is causal notes produce indifferent results.

Getting Organized

People often ask “with everything you are describing how are we supposed to take notes. I prepare an exercise document containing everything I think may be important to capture. In the middle of the exercise, it is far easier to fill in blanks than attempt to organize your notes.

Employing a Scribe

For important exercises it may be worthwhile employing a scribe. This allows you to focus on managing the exercise. It is essential to provide your expectations before an event begins so the scribe knows what points to focus on.

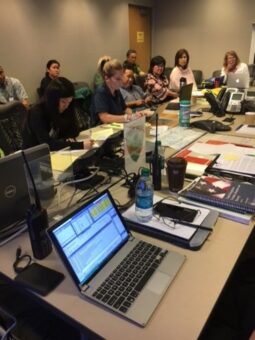

Photographs

Photographs can be very useful. They should be taken throughout the exercise. Periodic photos should be taken if you are employing gaming techniques such as a map, a dashboard, or a timeline. They are very useful for presentations or written reports about the exercise.

Engagement

Engagement

Social scientists have studied the phenomena of spontaneous order sometimes referred to as self-organization theory. This occurs in biology, people, and esoteric research such as artificial life. It certainly occurs in tabletop exercises.

Self-Organization

During a tabletop exercise a group of people are brought together to solve problems and make decisions. Self-organization can occur on several levels. They include people who are willing to get involved in the exercise, people who want to succeed (or avoid failure), and people who are willing to invest enough to complete the assignment at hand.

The familiarity of the people involved can lead to a second level of assigning responsibilities based on a person’s reputation or past performance. For groups involving varied levels of rank or authority, self-organization may fall along those lines. The use of self-organization techniques by the players may be part of the exercise or at odds with the goals and objectives. Self-organization may inhibit social learning where every player participates in problem-solving and decision-making.

Self-engagement

The goal of the facilitator is to move people from self-organization to self-engagement. This means they consciously choose to participate. During longer exercises there may be multiple opportunities to draw people out. This can be accomplished by engaging the players with questions as they work through particular problems or approach decision thresholds. (E.g., In this situation what is your number one priority and what decision can be deferred?)

In shorter exercises these opportunities will be limited. A simple technique is to allow the players to self-organize during the initial decision period. At the end of the period, I announce that during the hotwash the team will be doing a presentation explaining their actions. I often see people congratulating themselves on picking the perfect representative to lead the team.

I then inform the players that I randomly select the team member who will lead the team presentation. This is useful in several ways. Persons playing Wordle on their cell phones are suddenly very engaged. The natural leaders and organizers are engaging the players who have had little participation to this point. This type of technique is a simple solution for encouraging self-engagement and stimulating cooperation within the team.

Dealing with Problems

Dealing with Problems

The job of the facilitator is to keep the exercise on track. Part of the job is dealing with problems that occur during the exercise.

Process

An important part of the exercise process is ensuring the participants understand how the exercise works and their role within the exercise. A good practice is to provide introductory materials prior to the day of the exercise. This should be reinforced by a review of the exercise processes prior to the start of the exercise. This helps the participants focus on the purpose of the exercise.

Time

The facilitator must keep the exercise progressing toward the conclusion. Exercises often break down if participants are allowed unlimited time for discussions or even arguments about decisions. The facilitator must set limits and push the action forward.

People

You will rarely know the motivations of the individual players. People often attempt to control the direction of the exercise to further their preferences. There are hostage takers who attempt to direct the outcome to meet their objectives. Games often attract politicians who use the exercise to showcase their skills or advocate for a position. You may have gamesmen who attempt to manipulate the exercise guidelines or stoics who muddy the exercise climate by belligerent behavior. A good facilitator will observe the player dynamics and limit the disruptions these people may cause.

Environment

During your pre-exercise visit it is important to discover who has access and control of the location’s environmental systems. These include the heating and air conditioning, the restrooms, and access to additional power sources. Having this information will help to minimize disruptions during the exercise.

Interventions

A good facilitator focuses on interactions not interventions. Sometimes interventions are necessary to preserve the flow and content of the exercise. Interventions occur when the facilitator must use their position to interrupt the flow of the exercise. This may be necessary to preserve exercise integrity, prevent unsanctioned detours, or improper behavior by participants. This option should be reserved for serious problems. Constantly interrupting the exercise to correct minor problems can become an issue itself. Use interventions sparingly.

Adjudication

Adjudication

In wargames adjudication is a critical factor in wargames where combat results and effects have a profound impact on outcomes. Conventional wargames employ a rigid adjudication where rules impact outcomes and the facilitator implements them. A recent development is matrix games where the players debate the results of actions. Tabletop exercises employ three types of adjudication, free, semi rigid, and consensual.

Free Adjudication

In free adjudication the facilitator determines outcomes. Once a decision or action is taken the facilitator determines their effect. This type of adjudication requires a solid foundation of understanding of the exercise topic by the facilitator. In unfamiliar or technical topics, the facilitator may need assistance from a subject matter expert to evaluate decisions or actions. This provides the facilitator with a measure of decisional validation. It also keeps the participants honest and prevents potentially unrealistic outcomes.

Semi-Rigid Adjudication

One difference between a tabletop exercise and a wargame is the number of rules. Wargames are much more rigid with actions governed by rules. Tabletop exercises have fewer rules and are more flexible in problems-solving processes and decision making. If your tabletop has rules you must implement them.

Consensual Adjudication

Consensual adjudication is the simplest. Before the exercise begins the participants agree the facilitator will make the call regarding outcomes. To make this work the participants must be convinced the facilitator is a neutral arbiter.

Hotwash

The hotwash is one of the most overlooked parts of a tabletop exercises. This is where learning and sharing solidify into synthetic experiences. The greater the organization of your hotwash the more valuable the outcomes will be. There are three points the facilitator should consider: organizing the discussion, employing team presentations and encouraging self-examination.

Organizing the Discussion

The hotwash discussions should be organized to match the designer’s intent for the exercise. Of particular importance are the goals and objectives. At the start of the hotwash the goals and objectives should be identified as discussion points. The discussions should include a team presentation, individual comments and questions, comments by the observers and finally comments from the facilitator.

At the conclusion of the exercise, I recommend a short break and providing approximately 15 minutes for the exercise team to prepare their presentation. I remind the team in a real-world event the decision makers will eventually be called on to explain their actions. This is the concluding section of the exercise where they can practice explaining their actions. You should provide structure about what they should cover. In the section on engagement, I discussed the use of a randomly selected spokesperson to represent the team. This ensures everyone is engaged right to the end.

Encourage Self-Examination

The best hotwash does not consist of the facilitator grilling the exercise team. The facilitator must lead the discussion and encourage the team members to examine their actions. I recommend questions like, what was the toughest decision you made, what was the greatest dilemma you faced, and what action would you change? I have found that teams are much more critical of themselves than I would be.

End on a Positive Note

Tabletop exercises can end in a variety of results. Sometimes the results are not positive. Telling a team they failed will not provide anything valuable they can take back to the real world. They have developed synthetic experience and it’s mostly negative. The facilitator should emphasize the exercise was not designed to be easy. Since this was a simulated event there are no real-world consequences for mistakes or missed opportunities. This is the point where the discussion should be directed at how the team can improve or what actions will increase performance. I always complement the team for their efforts.

Closing the Loop

I finish by giving the participants an opportunity to ask me questions. I always provide my contact information. (This is where the business cards in your toolbox come in handy.)

Summary

Summary

People sometimes take a causal approach to facilitating tabletops. A tabletop exercise can be an excellent opportunity to train, evaluate, or plan future operations. By carefully approaching your job as facilitator you can provide an incredible learning opportunity for the participants. The key is careful organization both in your approach and delivery.