Iceberg Dead Ahead: Practical Tips for New Emergency Managers

by Roger Mason PhD

Often people are given an emergency management assignment with little or no preparation. For example, my career in emergency management began as a collateral duty assignment. I was a mid-level administrator in a municipal police department. My predecessor prepared me with, “Here are the keys to your office, good luck.”

Looking back twenty years, I can see where I struggled. Yet, I understand what tools and knowledge made a difference. There are six steps that will make a new emergency manager’s transition more manageable.

Step One: Understanding Priorities

One of the first things new emergency managers often say is “I do not know what to do first. There is so much to learn. I am overwhelmed.” The path out of this dilemma is prioritizing your responsibilities. If everything is equally critical, then nothing is critical. There are three priorities that an emergency manager should consider.

The second priority is the documentation that you have inherited. No matter how detailed or imperfect your documentation may be, you are now responsible for it. You must be an expert on what it contains. Documentation can be divided into two areas. They are the paperwork related to your activities, and the plans you will employ during an emergency.

The third priority is training. Training includes the training you need and the training you will eventually provide. You need to review what external training is available. Emergency management training is available at the local, state, and federal level. Be judicious in scheduling training, as you can spend all of your time away from your primary responsibilities. I strongly recommend taking as many of the online FEMA classes as possible. These courses can introduce a new emergency manager to a wide variety of topics. The best part is they are self-directed, so you can work them around your schedule.

Step Two: Due Diligence

My experience in emergency management is that many people are willing to help you but do not have the time to do your work for you. This means they expect you to do your due diligence. This comes in two forms, internal and external.

Internal

Internal

Internal due diligence means you must read every document in your organization directly related to emergency management. I have met emergency managers with over a year on the job who have never read their organization’s emergency operations plan. If a disaster occurs, you will be the person who is expected to be the subject matter expert on your plan.

You may have inherited plans that are obsolete. Do not worry about updating anything for now. Your job is to get a strong understanding of how things are organized. If your plans need to be updated that can become a priority as you gradually gain mastery over your organization and its operations.

External

I am in Southern California. Cities and counties in California fall under four levels of emergency planning, local plans, operational area plans, state plans, and federal plans. I would gradually work my way from the bottom to the top. Unfortunately, I never got this in any emergency management class I have taken.

Absorbing plans takes time. Pace yourself by including something new every day. After reading your local plans focus on the succeeding levels of plans that relate to you.

Step Three: Managing Time

You may find yourself overloaded with administrative tasks that have little to do with emergency management. Of course, you must follow orders and attend to them but try and carve out a few minutes to review something related to emergency management. This may involve sacrificing break times and lunches to expand your knowledge and develop your skills.

Step Four: Planning

Step Four: Planning

A competent emergency manager must be a planner. This means developing plans for requirements from emergency operations to training. Planning is directly related to time management. You must balance what you plan to do with the available time to accomplish it.

When planning, emergency managers should consider the three traditional operational levels of tactical, operational, and strategic. For example, US Air Force Colonel John Warden was the chief planner for the first Gulf War air campaign. His first step in planning was to look ahead and determine his preferred end state. Then he worked backwards identifying each step necessary to reach his final goal.

These steps become action items on the way to your goal. Col. Warden has written a book called Winning in Fast Time. He asks when managing your time what you are doing at the tactical level (this week) to make an immediate improvement. What are your operational goals (six months) and how are your weekly tactical goals supporting it. Finally, what are your strategic goals (one year out)? How do your tactical and operational goals support your yearly strategic goals.

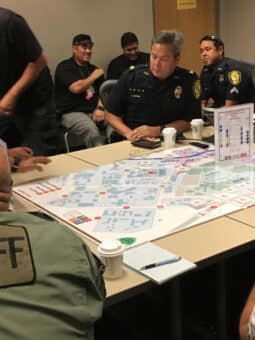

Another challenge is coordinating with other plans and schedules. Your first week on the job you should check the master calendar of your agency and any related agencies. There are some events you need to attend and some you may be responsible for. You need to know about things like an annual multiagency tabletop exercise that you are responsible for.

Step Five Developing Basic Skills

Technical Proficiency: You should be proficient with any technical system your organization intends to employ during an emergency. There will be no time to look for a manual once an emergency occurs.

Access Tools: You need to have immediate access to any type of log in or certification to access online systems. This is especially critical if you are responsible for an emergency asset like a community alert system.

Verbal/Concept Proficiency: This can be developed during your self-study efforts. You need to understand the vocabulary and the vernacular employed by your organization and the organizations around you. It might be useful to print out the basic FEMA emergency management glossary. Learning the language and developing a basic understanding of essential concepts is essential.

Communications/Presentation Skills: You should be familiar with Microsoft Office 365. This includes the programs you will use like Word, Excel, and PowerPoint.

I also recommend learning Visio. Microsoft Visio allows you to draw diagrams and charts simply and easily. Visio will professionalize your memos and papers and engage your PowerPoint audiences.

Summary

Getting started in emergency management is a daunting task. You are faced with

a steep learning curve. The challenges increase when you realize a disaster could occur tomorrow. There is one more step that can help. Find trusted mentors and peers who can provide advice, direction, and wisdom. This will make the iceberg just a bit more manageable.