Operational Wargaming: A Cautionary Tale

by Roger Mason PhD

Introduction

Introduction

There has always been an attraction to operational wargaming. Throughout history, wargames have been used to prepare, refine planning, and solve problems during operations. Wargaming is a valuable practice in business, political, and military affairs.

Practitioners have attempted to use them to prove results, justify hypotheses, and validate outcomes. Universities like King’s College, London and Georgetown University have opened centers to study wargames. In 2015 the US Department of Defense decided to overhaul its wargaming capability to improve operational planning. People believe that any shortfalls can be overcome. The lure of wargaming remains strong.

Conventional wisdom suggests the predictive and operational value of a wargame depends on how carefully it is designed. However, in 1971 a group of the world’s greatest experts gathered to wargame a problem of infinite possibilities. These experts recognized that the results would have profound political, social, and personal stakes. For six months they analyzed and gamed every aspect of the upcoming campaign. Despite their efforts, they were badly defeated. This article explores what went wrong and lessons from which wargame designers can profit.

Historical Examples of Operational Wargaming

The history of operational wargaming has a long history. For centuries wargame designers have sought games that solved problems, offered training, or provided a glimpse of the future.

Games that Failed

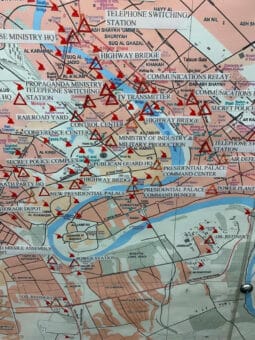

When historians discuss unsuccessful games two examples come to mind, the Imperial Japanese Navy Midway game and Sigma 64, the US Defense Department’s Vietnam wargames.

The Midway Game

Admiral Yamamoto, commander of the Japanese navy, convened a series of wargames in May of 1942. The purpose of the games was twofold. First, to introduce his plans to capture Midway Island and secondly to review the strategy for destroying the US Navy carrier fleet. Several of the participants survived the war. Their memories provide insight into the wargaming practices of the Japanese. One problem was the habit of umpires to revise unfavorable game outcomes in favor of the Japanese players.

During the Midway game, two Japanese carriers were sunk due to a random result. Some of the senior participants had two objections. First, they decided the American fleet could not be in position make such an attack. Secondly, they believed land-based forces could not have successfully conducted such an attack. Unfortunately, the Japanese assumptions about the possible proximity of the American fleet were incorrect.

In 1964 the US Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency conducted a series of wargames designed to investigate expanding the US involvement in Vietnam. The game was intended for senior decision-makers. In the first game, all the senior level participants deferred to staff members who represented them in the game.

The game was played, and the inescapable conclusions were obvious. The US would be gradually drawn into a stalemate. The air campaign to cripple North Vietnam would not be decisive. Instead of victory the ground war would result in increasing losses that would become politically unacceptable. Suddenly, the game had everyone’s attention.

The game was replayed by senior-level decision-makers. Key factors were changed based on a new set of assumptions. The second game resulted in a much more favorable outcome for the United States. Unfortunately, real-world events would prove the original outcome was much more accurate.

Inconclusive Games

Inconclusive games are interesting because they were inconclusive for many reasons. Some games were inconclusive because of how they were evaluated, and their results employed.

In 1941 the German Army conducted a wargame to determine the feasibility of supplying an invasion of Russia. Ironically the wargame was under the direction of General Friedrich Von Paulus who would later surrender the 6th Army at Stalingrad.

The game investigated the challenges of maintaining logistics over long distances in a country with weak infrastructure.

The game revealed logistics would be very difficult to maintain if the campaign was prolonged. The logistics game was a follow-on exercise to an earlier wargame focused on the land campaign. The first game had predicted a blitzkrieg that would easily defeat the Russians. Adolf Hitler was reportedly enraged by the results of the logistics game. He pointed to the contradictory conclusions as key indicators of the failure of wargaming. Hitler forbade further strategic level wargaming.

Games That Worked

While there are plenty of examples of inconclusive games or failures there are certainly games that were very successful. They were games used to solve problems and develop winning strategies. Some accurately predicted future events.

Western Approaches Tactical Wargames

From 1939 through 1941 the British suffered severe losses to their merchant fleet from German submarine attacks. In 1942 retired Royal Navy Captain Gilbert Roberts was recalled to active service, Gilbert was ordered to investigate the convoy problem and develop a solution. His answer was the Western Approaches Tactical Unit. Gilbert conducted a study of convoy operations and developed a wargame system employing German submarine tactics.

Gilbert’s team developed wargames to evaluate the situation and test possible counter-measures. Convoy captains were trained using the game. The Royal Navy used the results to modify their strategy. Convoy losses rapidly decreased.

The conventional history of World War Two is Stalin refused to believe Germany would invade Russia. This has been disproven by firsthand accounts provided by Russian generals like Georgy Zhukov. In Zhukov’s autobiography, he reveals the Russians had intelligence about the German plans to invade. A series of wargames were prepared to study the problem. The games were played by the commanders in charge of the areas included in the game.

The Russian general staff was split between two strategies, whether to commit everything to defend the border or employ delaying tactics combined with a defense in depth. The first wargames indicated a border-centric strategy could not succeed. The staff then wargamed a delaying plan. The second game showed it would be possible to stop an invasion by delaying the Germans until winter began.

The games revealed any German penetrations would gradually slow due to logistic problems. (The same conclusion from the 1941 German game.) Large Russian troop formations would be bypassed and captured. Further delays would occur while the invaders maneuvered to capture the surrounded Russian armies. The delaying strategy developed in the wargames was adopted by Joseph Stalin and became the basis for Russian strategy in World War II.

1972 Chess World Championship

In 1969 Boris Spassky won the world chess championship from Tigran Petrosian. In 1972 his opponent was the American chess champion Bobby Fischer. Fischer had won two qualifying tournaments to face Spassky for the title. For six months both sides prepared for the final match.

Wargaming for Infinite Possibilities

There are many challenges in using wargames to develop a strategy for a particular problem. None is more significant than a problem with potentially infinite possibilities and outcomes.

Chess is a game of endless possibilities. American mathematician Claude Shannon calculated the number of possible chess moves at 10120. The problems begin as soon as you start the game. Some experts believe there are 400 possible opening moves. These moves are usually related to approximately 40 opening strategies for white or black in competitive chess. During the opening of a game, the number of potential moves rapidly expands into over a100,000 possibilities.

The goal of an opening strategy is to gain the advantage for the next phase of play known as the middlegame. The advantage comes from seizing control of the middle of the board and positioning pieces to dominate your opponent. By the middlegame tens of millions of moves are possible. It is during the middlegame where attacks on the enemy begin. Again, the goal is to dominate your opponent setting them up for the endgame.

During the endgame the number of playing pieces declines due to combat. Players attempt to promote remaining pawns and attack the opposing king. Ultimately chess strategy is about gaining the advantage while preventing the course of play from spinning off into unfavorable, unknown, and uncontrollable outcomes.

The Ultimate Chess Team

Since 1948 the chess world championships had been dominated by Russia. The Russians were the reigning world champions and determined to maintain their dominance. Boris Spassky had been the runner-up in 1966 and the winner in 1969. The Russians were determined to retain the crown and began developing a team to support Spassky. The Russian support team was the dream team of chess.

Persons with experience as international tournament players were selected for the team. Anyone who had either played against Bobby Fischer or studied his matches were especially important. The team included former world champions Tigran Petrosian, Vasily Symslov, and Mikhail Tal. Russian grandmasters Baturinsky, Keres, Korchnoi, Semion, Furman, Stein, Taimanov, Kotov, Nei, Karpov, Krogius, and Geller were also included.

The team was supported by specialists Boleslavsky, Poluganevsky, Shamkovish, and Vasukov. The specialists were experts who had carefully studied the approximately 500 tournament games of Bobby Fischer. The Soviet Science Academy and the newly opened Soviet Chess Lab were asked to participate. The coach of the team was Russian Grandmaster Igor Bondarevsky.

Coach Bondarevsky established three main branches of preparations: psychological preparation, physical preparation, and chess preparation. The large number of experts allowed for the simultaneous analysis of many scenarios. The team was divided into primary and secondary lines of inquiry to ensure nothing was overlooked. As their analysis was developed they repeatedly gamed every aspect.

Evaluating the Competitors

The Russian team conducted a detailed evaluation of Bobby Fischer. Their observations would form the basis for the strategy developed to defeat him. They concluded:

- Fischer was a very decisive player. He rarely used the full time allowed for his move.

- He had superb calculating abilities.

- He possessed the best opening game tactics in the world.

- Fischer was overconfident in his opening game.

- Fischer was inflexible and always opened the game using a limited number of strategies.

- Fischer will sacrifice the opportunity to gain a ½ point in a drawn game to gain a full point in a win.

- Fischer is psychologically weak evidenced by his habit of being difficult with match organizers and demanding in his preconditions for tournament participation.

A similar evaluation was done of Boris Spassky. This evaluation determined:

- Spassky was strongest in the middlegame and probably a better middlegame player than Fischer.

- Spassky had beaten Fischer on three previous occasions.

- Spassky was much stronger psychologically.

The team consensus was Fischer was dangerous but beatable.

Gaming the Outcome

The first step was a careful analysis of the two player’s tactics. This included analyzing Spassky playing from Fischer’s perspective. Fischer’s openings were studied in detail. Different situations were repeatedly gamed. Coaching team members were assigned to play as Spassky and Fischer in a wide variety of potential situations. Spassky was asked to observe the games and participate in the analysis. Spassky played simulated opponents who employed Fischer’s tactics.

Final Conclusions

After months of gaming and analysis, the coaches provided their final observations and recommendations:

- Fischer was brilliant but limited to a handful of openings. He will not deviate from them.

- Fischer is uncomfortable improvising and will provide no surprises.

- Fischer will not play for draws but always plays to win.

- Fischer can be psychologically manipulated if he has a bad start.

- Fischer is too brilliant to be directly defeated but is vulnerable with a combination of wins and draws.

The Match

The match began on July 11th in Reykjavik, Iceland.

The Russian plan was to force Fischer to play against the combined strength of the Russian chess federation backed up by several science academies. There were four points to the Russian strategy. First, prepare Spassky with winning solutions to Fischer’s traditional openings. Second, manage the match flow of wins and draws to ensure Spassky was always progressing toward victory.

Third, employ the Russian advisory team to analyze the flow of the individual matches and advise Spassky on the best solutions. Finally, in difficult situations requiring more analysis the team physician could declare Spassky unwell. The rules allowed for a delay for him to recover. This would provide the advisory team to develop a solution and allow Spassky to rest.

Fast Start

Fischer provided clear indications his track record of making demands and changing his mind would continue. Fischer made numerous complaints about everything from the types of chairs to the lighting in the exhibition hall. The Russians took this as an indication of Fischer’s fragile mental state. Fischer failed to attend the opening ceremonies of the match.

After apologizing the championship finally began. Fischer lost the first game by attempting to win when a draw was the safer choice. He then complained about the conditions and forfeited the second game when he failed to appear for the match. Fischer had not deviated from his traditional openings in the first match. His failure to appear for match two seemed to confirm his psychological fragility. The Russians were convinced Spassky would cruise to victory.

In game three, Fischer opened with a strategy he had never employed catching Spassky completely unprepared. In match after match Fischer deviated from his traditional moves. He played so rapidly the Russian advisory team was unable to effectively communicate with Spassky. In the next 17 matches Fischer stunned the Russians by playing for draws 11 times and losing only once. Bobby Fischer proved every pregame conclusion wrong. Spassky was crushed.

What Went Wrong?

The Russian preparations for the 1972 Chess World Championship was one of the most carefully gamed problems in modern history. Everything that a dozen experts had considered had been included. Fischer’s preparations were in sharp contrast to the Russian effort. His support team consisted of a few friends from his chess club in New York. He studied a chess book about famous matches and a friend’s notebook about Spassky’s greatest games. He played a handful of preparation matches.

The Russians threw the entire weight of their country into the preparations. Every contingency was repeatedly gamed and analyzed. How could the Russian efforts have gone so wrong?

The Russian chess federation fell into a series of pitfalls. During the preparation phase and the match problems appeared. The same pitfalls can lead wargame designers into misdirection, faulty conclusions, and mistaken outcomes.

Dangers of Group Think

The Russian team agreed regarding the strengths and weaknesses of Bobby Fischer. As they dove deeper into their preparations, their opinions became more solidified. They lacked any process to include or debate divergent opinions. The Russian team consistently failed to investigate a range of contradictory hypotheses.

In Nikolai Krogius’ biography of Boris Spassky there is a description of the six month preparation period. Krogius noted the team’s inability to investigate the unknown. They consistently defaulted back to what they believed they knew about Bobby Fischer and played those scenarios over and over. They were not interested in investigating unexplored possibilities.

Inability to Identify Bias

The Russian dream team had the greatest chess minds in the world, but they failed to identify their personal and group biases.

Lack of Validation

The preparation efforts lacked validation beyond the team member’s opinions. The team self-validated their opinions, confirming them with the design and direction of the preparations.

What Can We Learn?

Four lessons can prevent wargame designers falling into the Russian Chess Federation’s trap.

Wargames are amazing tools. They can be used for a variety of purposes. A well-designed wargame can facilitate understanding and provide new perspectives on complex problems. No matter how valuable a wargame is it remains a tool. Tools have limitations.

The Russian coaching team was convinced that they could predict players actions and manipulate the outcomes to victory. Wargames are unreliable in predicting the future. They become unwieldy when overburdened with expectations. Recognizing a wargames’ limitations and adjusting your expectations can prevent mistakes.

Balance Your Bias

The answer to bias is not to eliminate it but rather to balance it. This is best accomplished by recognizing it exists and ensuring it does not overwhelm your design. The Russians never considered its possible effects. Some bias can be good. Bias can represent experience and knowledge that can enhance your game. The proper amount of bias can lend a unique flavor to a game. Bias that takes over can also lend an odor that is less appetizing. Bias unchecked can lead to imperfect results.

Wargame designers must resist the temptations common to wargaming. Like all illusions chasing them can become irresistible. Wargame temptations include using the game to prove a theory, to direct an outcome, or change opinions. A well-designed wargame can accomplish all three. Problems arise when your purpose is baked into the design. The depth of the Russian preparations eventually became examples of irrefutable evidence they were unbeatable.

Seek Validation

Wargames cannot be validated in the same way as a repeatable scientific experiment. Wargames can be validated by face validity, content validity, and construct validity. Face validity means the game or exercise accurately models a real-world event.

Content validity means the content or data the game is based on is accurate. Construct validity refers to how precisely the game models the factors which define the topic. Consensus amongst the game designers is not validation of the design.

Summary

Summary

Right now, wargame designers are developing operational games. From analyzing problems to predicting the future, wargamers will be looking for answers. When evaluating the preparations for the 1972 world championship it is easy to wonder if wargaming really matters. Like many failures, it is simple to blame the methodology and not the application. This story proves that more wargaming is not always better. What matters is better wargaming.

Author’s Note: I intended to include photographs from the Fischer Spassky matches. Only a few photos were taken due to Bobby Fischer’s insistence that photographers be banned. The rights to these rare photos are very expensive so they do not appear in my article.

Summary

Summary